Did Teachers’ Workloads Increase After the Pandemic?

Some teachers feel that their workloads increased after the pandemic.

March 27, 2023

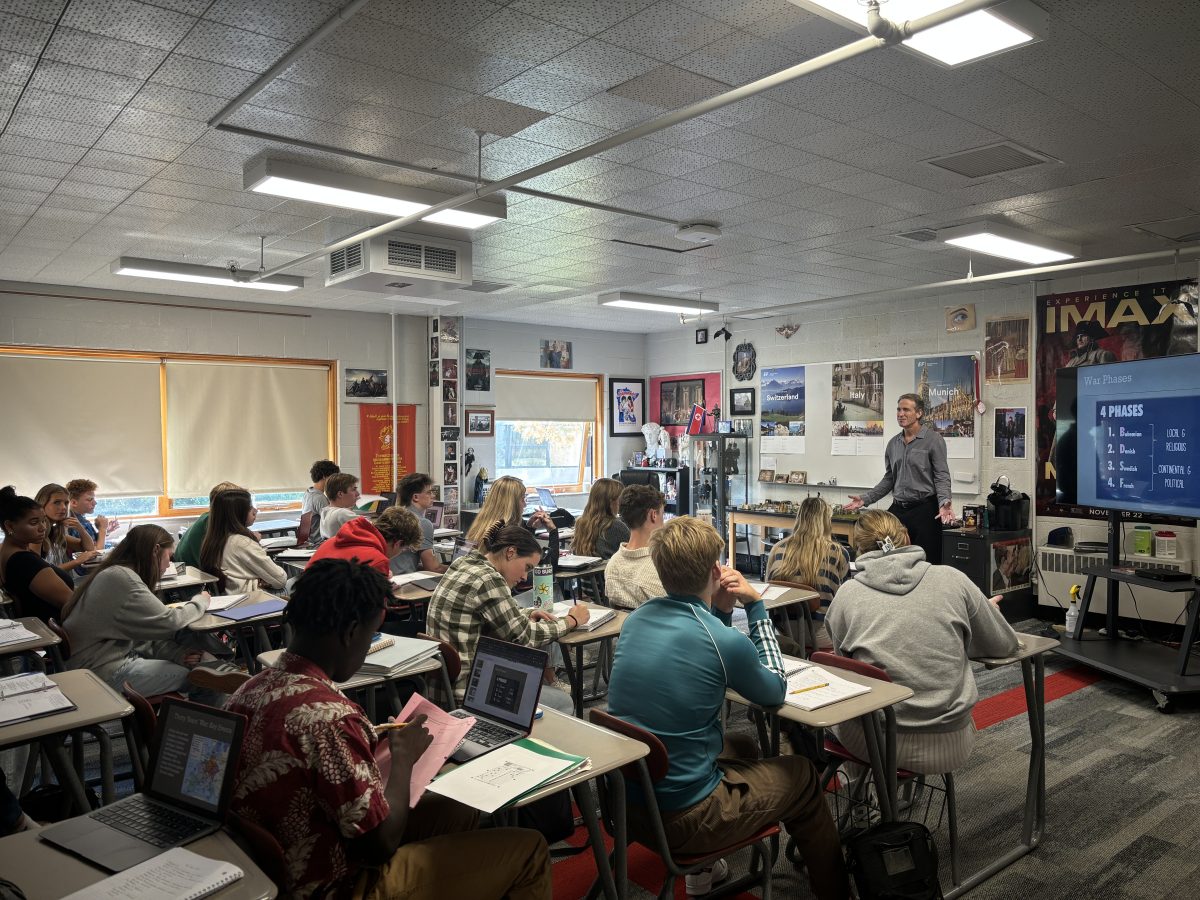

At BSM, teachers are contracted to work from 7:30-3:00. Outside of those contracted hours, teachers spend time grading, preparing for class, and working with students individually. Many teachers also help coach sports teams, run clubs like speech or Model UN, and serve on faculty committees.

These additional tasks have always been part of teaching, so many teachers expect the extra workload. However, many teachers feel that new administrative tasks, extra school events, and prefect duties have become unmanageable.

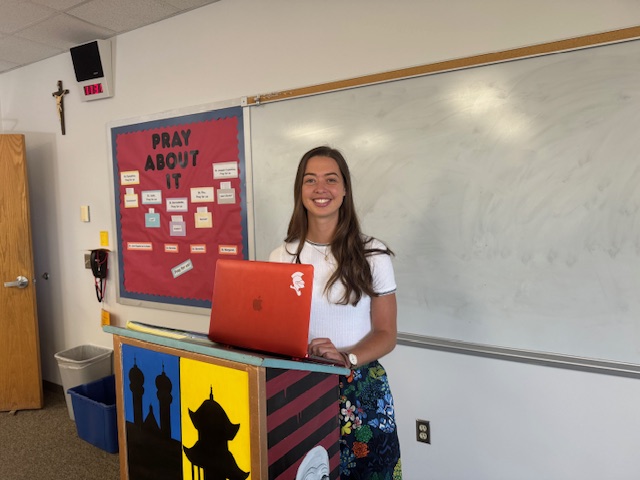

“I think the biggest thing that takes time away from prep during the day would prefecting duty. I’m in the cube with 35-40 other students who aren’t necessarily quiet. Keeping track of who’s gotten past and who’s going to the bathroom doesn’t allow a ton of time for prep work,” Theology teacher Michael Becker said.

Teachers still have a prep-hour, but it’s not always reserved for prep or grading. “The prep hour that is given to teachers is never really a proper [prep hour], it’s kind of a catch all for everything else that we have to do. When we’re asked to supervise activities that were planned by other people who don’t carry classes, that really cuts into our time,” English teacher Anne Marie Dominguez said.

Many teachers attribute this change in workload to the pandemic. “I think during COVID the amount of daily work that we had increased in general. The amount of work we do online, including emails, posting things online, [digital copies], and expected email communication with a 24 hour turnaround has added over the years and changed expectations with [the pandemic],” Becker said.

The heavy workload pushed some teachers to leave the profession altogether. “I’ve been teaching in one place or another for 20 years, but during the pandemic, I started to seriously consider leaving teaching. I updated my CV and submitted a few applications. The half virtual year was ridiculously hard; it was honestly triple the work to try to prepare classes that functioned reasonably well with some students online and some in person. I was very, very close to leaving at that point, and if I had found something that met both my salary and schedule needs as well as my sense of doing something meaningful and intellectually fulfilling, I would have left without hesitation,” English teacher Tiffany Joseph said in an email interview.

After the pandemic, many teachers felt the workload did not return to normal. “I expected the following year to be a little easier, but it wasn’t. We were all in person but there was a lot of residual frustration…The workload was definitely a big part of looking for a new career. English teaching already has huge grading load. I only teach 4 classes instead of 5. In other words, I take a pay cut to have a part time assignment in order to try to only work full time hours…and I still have to do work outside of school. When you take this already daunting workload and add in the additional expectations and responsibilities that seem to keep trickling in, sometimes it’s hard not to think about other employment. There is a lot of unpaid labor in teaching. I didn’t go into teaching to make a ton of money obviously, but when work kept piling on during the pandemic, it got harder and harder to justify what I was doing. Then, once I considered the possibility of leaving, it never totally went away. As long as I am teaching, I’ll stay at Benilde, but other careers sometimes seem enticing,” Joseph said.

This uptick in workload is not isolated to BSM. Theology teacher Nathan Schlepp taught at Holy Family Catholic high school before coming to BSM, and he saw a similar rise in work. “The amount of things that got put up on a Schoology platform or online, and it became oftentimes double the work because a lot of teachers didn’t use those platforms before [the pandemic],” Schlepp said.

Compared to public school teachers, private schools don’t have unions to strike or advocate for working hours. “In public schools, you have unions that do a lot to protect the workload and make the pay commensurate with what you are actually doing,” Dominguez said.

Robin Nyquist has worked at Buffalo Middle School for 11 years as a sixth grade social studies and technology teacher. After the pandemic and with the recent teacher shortage, she has also faced a bigger workload. “Recently with no subs, we have to cover more classes…if there’s no subs and we have to [use] our prep,” Nyquist said.

At public schools, teachers unions protect contracted hours and prevent the administrations from adding unpaid work. “If you take on extra duties, usually you get paid for it. If the administration tells you you have to [without extra pay], then you can file a grievance with your union,” Nyquist said.

Although it’s more difficult for public school administrations to increase teachers’ workloads, many of them have less prep time to begin with. “We have a 52 minute prep school every day. But often that’s taken up with meetings or dealing with other things that are not prep time. I would say 90% of my prep is done outside of school hours,” Nyquist said.