Curriculum Challenges

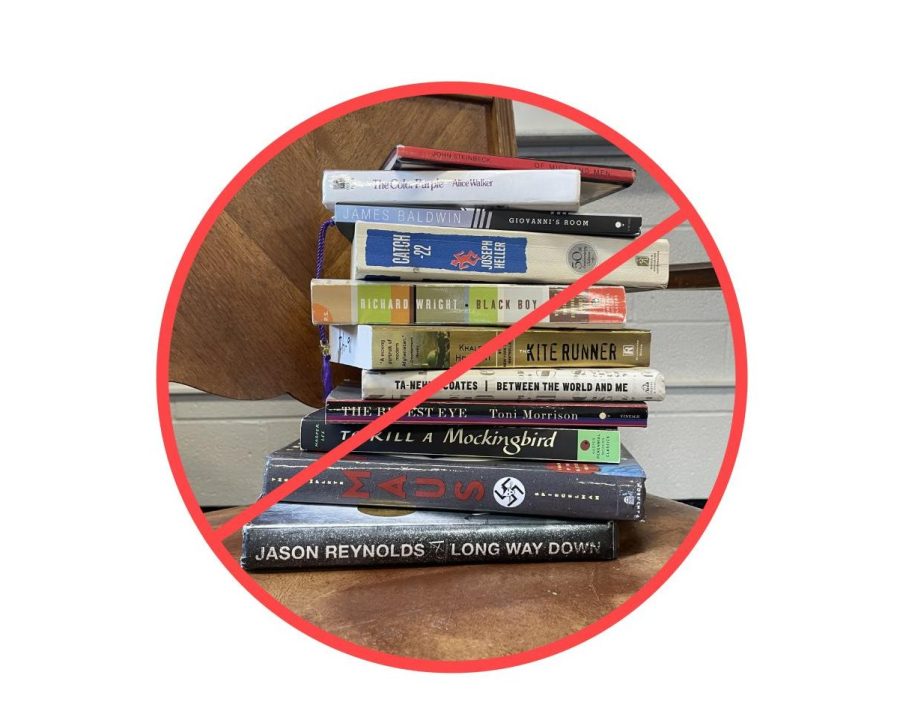

Some of the different books within the curriculum that have started controversy.

Across the nation and within BSM, there has been a wider push to censor curriculum and books that deal with controversial themes.

English departments are often specifically targeted by these curriculum challenges. At BSM, two ninth grade English books have been called into question by parents: Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck and Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds. Of Mice and Men is a classic about a man with a mental disability, Lennie, and his best friend, George. Long Way Down is a contemporary novel, written in verse, about gun violence and young adults.

“Long way down as a young adult novel, and it’s written in verse. We read it for many different reasons, not only because we like to study poetry… We want it to be interesting to kids. But because it does deal with the problem with gun violence, I think some people are alarmed at the idea of having books that bring up topics of social justice,” Belanger said.

Of Mice and Men is a part of a trio of novels in the ninth grade English curriculum that focus on social justice. As a Catholic school, these social justice books give students a lens to explore integral pieces of Catholic social teaching, like the rights of the most vulnerable and oppressed.

“The English department has always been able to rely on the Catholic Social teachings as a lens through which we view any text. If there is a social justice issue, in other words, an issue that reflects the inequality in society around social issues like gender, class, race, economics, whatever it may be, we can use our Catholic identity to discuss this,” Belanger said.

Part of the problem with banning books is that it limits the content and ideas students have access to. As a college prep-school, BSM’s goal is to expose their students to different learning materials and ideas they may encounter in higher education.

“When you put books in front of people, you’re better equipping students to understand the world around them, to face the future, to have conversations to learn about people and cultures and environments that they are not familiar with. And that’s what we do as a college prep school as we are preparing our students for college and beyond and sheltering students from conversations that deal with real world issues isn’t helping them,” Belanger said.

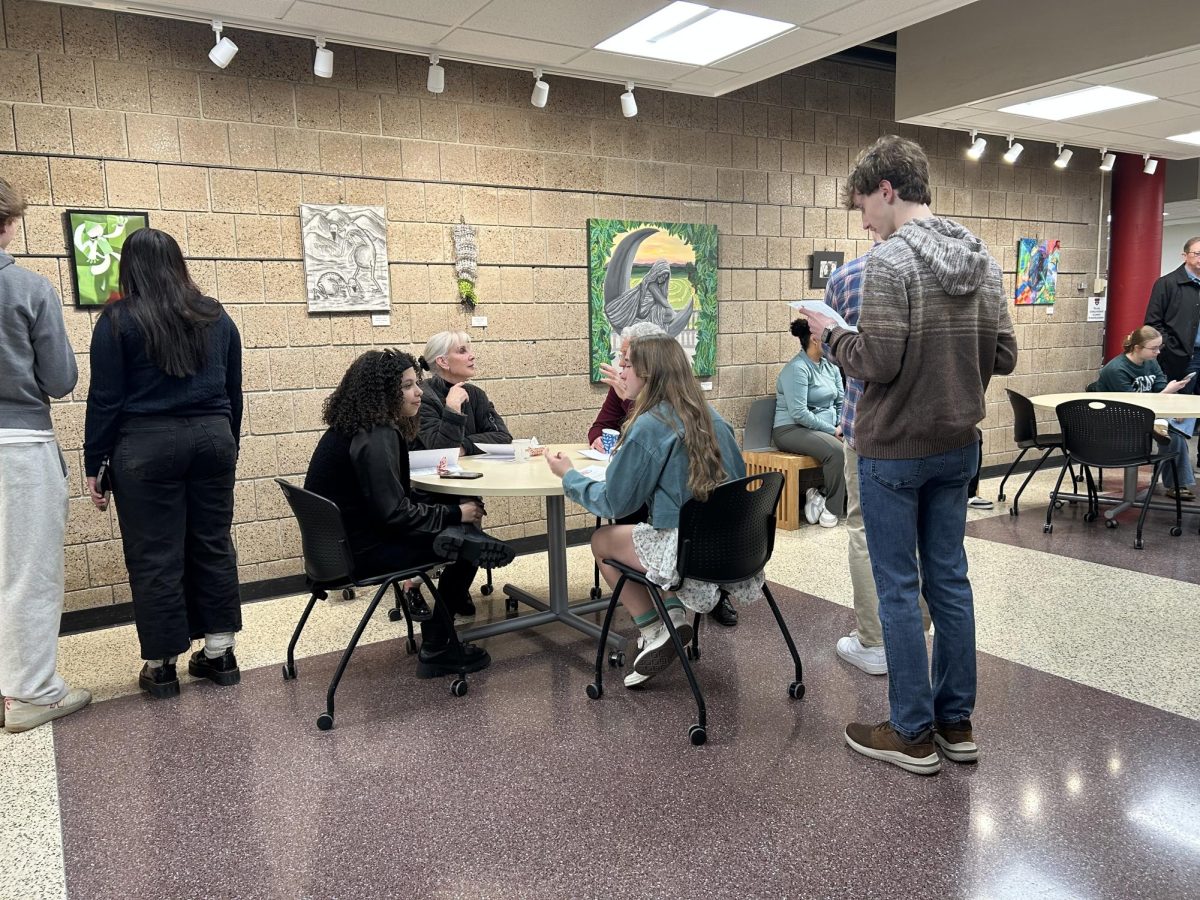

So far, the curriculum challenges at BSM have been relatively tame. The English department has responded to criticism by emailing the parents and discussing the purpose and merits of the books being challenged. “[We’ve responded] usually just in an email or a conversation with the parents. These challenges don’t alarm me because I believe in the power of the books themselves,” Belanger said.

Although the school does not have an official process in dealing with these curriculum challenges, the administration and staff are confident in teachers’ abilities to handle parent concerns.

“We have some of the best teachers I’ve ever seen, and I’ve been to many schools. I think they’re able to have these critical conversations..when it comes to parents having questions about what is being taught in the classroom, the teachers have a lot of autonomy to make these decisions,” Director of Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging Dennis Draughn said.

Draughn hopes that the parents challenging the curriculum will learn to share this trust in the teachers. “I would hope that families on the outside start to gain trust that us as professional educators know what we’re doing, and know that we’re here to enrich students and prepare them for global society. If we’re only single minded and we’re only limited in what we’re teaching them, then we are not preparing them for society,” Draughn said.

Even though the BSM challenges haven’t affected the curriculum much, some are worried about the nationwide push for censorship. In libraries and schools across the country, parents are petitioning to remove certain titles. In fact, some groups have gone as far as proposing state legislation to remove books from public schools.

In Minnesota specifically, a bill was recently introduced to the Senate that would require teachers to share curriculum with parents. The Star Tribune reports that this legislation “echoes measures nationwide that seek to limit what public schools can teach.” This comes after Wisconsin’s governor vetoed a bill banning critical race theory in schools. Other states have proposed bills with lists of buzz words and books that cannot be taught in schools, like in Oklahoma, Texas, and Tennessee.

One book that has gained national attention is Maus, a graphic novel by Art Spieglemen. The novel shares Spieglemen’s father’s experience in a concentration camp during the Holocaust and how it affected him later in life. At BSM, this book is taught in tenth grade English.

“Banning a book like Maus is extra absurd in my opinion, because it carries such a great cultural value in looking at not just history, but a really great lens at how we can examine visual rhetoric in writing, as well as the ramifications of what happens if we don’t pay attention to history and learn from humanity’s mistakes from the past,” English teacher Keanan Faruq said.

For many educators, these challenges are worrying because they force a single perspective on students, instead of giving them the opportunity to explore curriculum for themselves. “We need to just teach the truth…provide a space where we can have these critical conversations and not let one narrative be the truth,” Draughn said.

Oftentimes, the people or groups challenging the curriculum do so without understanding how the books are being taught or why they are valuable. Some teachers think that if parents were to immerse themselves in the curriculum and class as a whole, they would understand that each book taught serves a different purpose.

“Pushback does come from people who have only heard maybe alarming things about an author or alarming things about the content and haven’t spent time with the book yet. Or perhaps they’ve read the book and don’t understand why we’re using it or how we’re using it,” Belanger said.

Instead of rushing to challenge a book or contact the school, it can be valuable for parents to discuss reading material with their children. “I encourage parents to talk with their children about what they are reading; this can open up great conversation and lead to valuable teaching opportunities,” Librarian Laura Sylvester said in an email interview.

![Teacher Lore: Mr. Hillman [Podcast]](https://bsmknighterrant.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/teacherlorelogo-1200x685.png)