Why Do Students Struggle to Read?

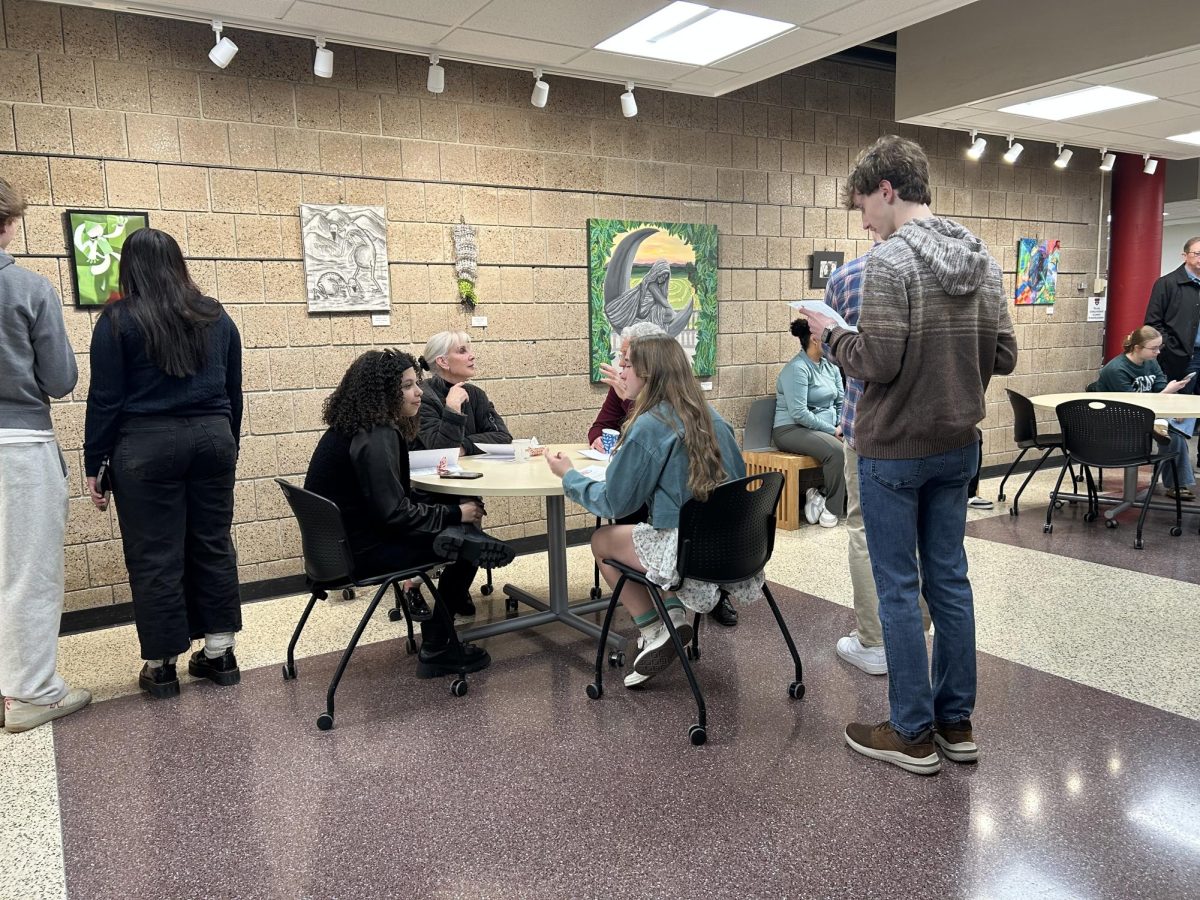

Many teachers at BSM have noticed a decline in reading comprehension skills among students in recent years.

February 3, 2022

In recent years, BSM teachers have noticed a steady decline in students’ reading skills and corresponding comprehension and writing abilities.

Reading is a crucial part of many different classes at BSM. In social studies courses, students read from textbooks to complete assignments. English classes revolve around reading both non-fiction and fictional texts. Even courses that aren’t traditionally associated with reading depend on these skills.

“Even in talking with math teachers just about this informally, you know, you have to be able to read story problems really well. And to comprehend them in order for you to understand what calculations needs to be done,” English teacher Anne-Marie Dominguez said.

In prior years, Chemistry teacher Abbi Baker would assign students textbook readings and assume they could synthesize the main idea and answer questions about the reading. Now, she has found that students are struggling to understand what they read. The answers to her questions reflect this struggle.

“Now that’s always a spit back from what’s in the text or trying to define a word. They’re always using the exact same words and not being able to think about it, formulate their own idea, and then explain it to someone else…rote memorization is easy for students now versus thinking about what they’re reading,” Baker said.

For many teachers, students’ decline in reading comprehension has meant a change in lesson plans and teaching strategies. “I used to use the textbook a lot more. Now I have done more video lectures…When they’re in my class, I try to get them working on things like reading. If they don’t understand the question, I answer with a question like, let’s look at what you’re reading again. What does it say here? What does it say here? Now put that together. I’m helping them with their reading skills,” Baker said.

Even in advanced classes, teachers are spending longer guiding their students through reading assignments. “When I first started teaching AP Euro, for example, I could come into the classroom and say this is how we do a document based question. I could show them how to do one and then turn them loose to write one… they could do most of it. I didn’t spend that much time teaching how to put it all together. And now, I spend a month… time I didn’t have to spend before,” social studies teacher Cherie Vroman said.

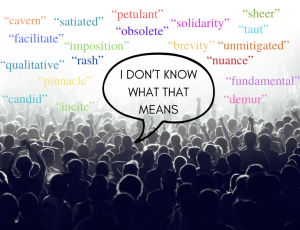

Other teachers have noticed specific issues with student’s vocabulary. In order to comprehend difficult texts, students need to be able to understand the textbook’s lexicon and key terms. “Unfortunately, students seem to have a harder time stringing together arguments or even when they write that paragraph, getting thoughts to connect, and to show the connections. Even their vocabulary… I’ve watched them struggle because they can’t even find the right word they want,” Vroman said.

This decline mirrors national trends. In 2019, the New York Times reported that national reading scores declined in half of US states. Peter Afflerbach, an expert on reading and test scores from the University of Maryland, said that “the students haven’t developed the reading comprehension to deal with text complexity.”

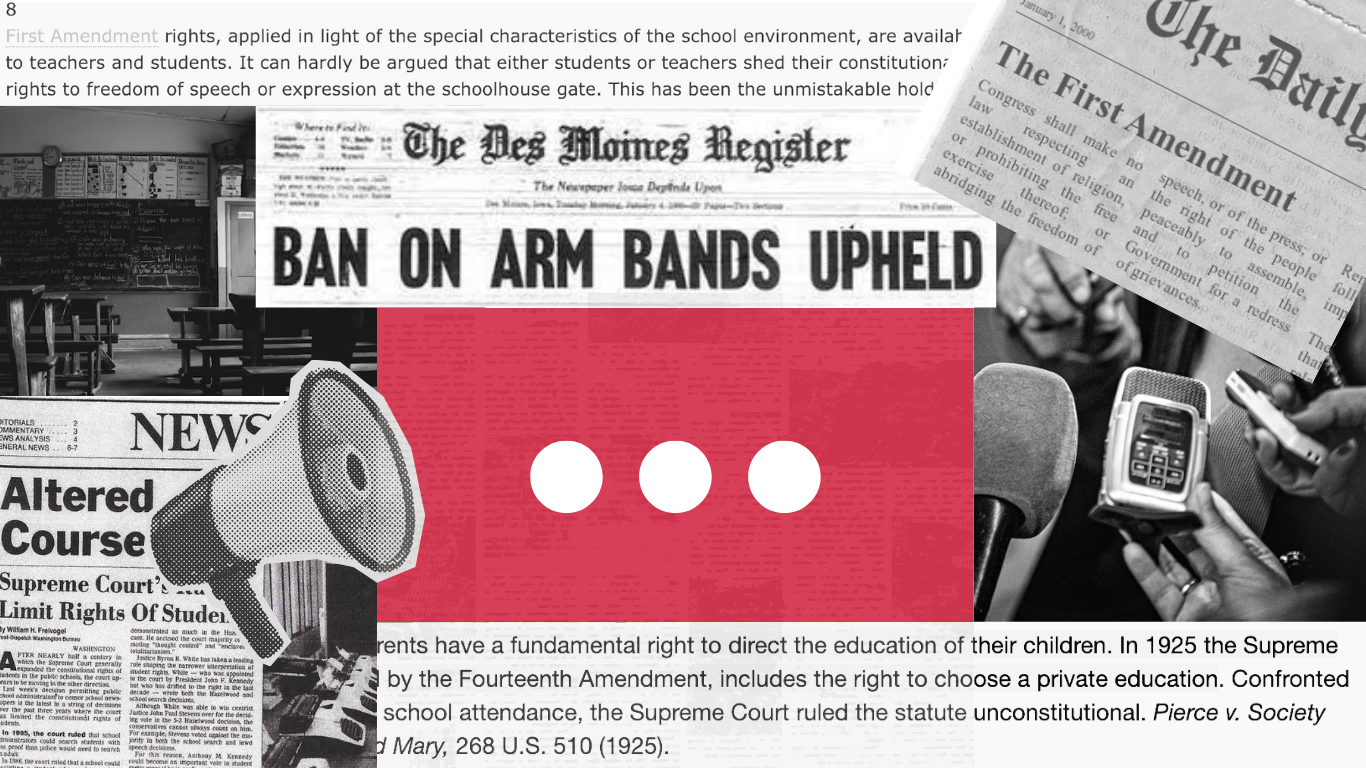

Consequences of worsened reading comprehension extend beyond the high school classroom. As a college prep-school, BSM is particularly concerned with standardized test scores and the ACT. The ACT has a reading section to test students’ comprehension, but reading skills are also key to completing the math, science, and English sections.

“There are charts or studies done that have shown that there’s a direct correlation to students reading just 20 minutes a day and their ACT scores…on the ACT, you are reading directions, you are reading problems and stories and all of that requires understanding comprehension,” Dominguez said.

Although standardized tests do include reading comprehension skills, they might also be part of the problem. In order to fully understand what they are reading, students need some background knowledge on a variety of topics.

“I think with social studies, in particular, in the last I don’t know how many years, the standardized tests have been emphasized… In some areas of the country, we sacrificed social studies curriculum because we want to get our reading and math scores. So then you have students coming in to read the social studies nonfiction texts who didn’t have as much background so you don’t have that background knowledge to connect to,” Vroman said.

The BSM teachers have a few theories on the reasons for this decline. Primarily, they blame it on the correlating decrease in students reading for pleasure. “There is a correlation between the drop in students reading for pleasure and their ability to read well in school. And there’s a direct correlation between being able to read well and writing well because you absorb all the rules and what sounds right in your mind, even if you can’t cite the rules,” Dominguez said.

This theory checks out with student behavior. In a survey sent out by the Knight Errant, over a third of students responded that they never read for pleasure. An additional 22% of students said they only read for pleasure less than thirty minutes a week.

“I think the number one reason is [that] students just don’t read as much for pleasure. Because there’s so many things competing for time, right? You’ve got social media, just electronics, computers, and all that,” Vroman said.

In order to alleviate this problem, BSM can encourage students to read outside of the classroom. It may be hard for students to find time to read, given the time that they devote to homework and extracurriculars. Homeroom could potentially be a time where students can devote twenty minutes to reading books of their choice.

“It could be during homeroom…for two or three days this week, all you’re going to do is just read what you want to read,” Dominguez said.

![Teacher Lore: Mr. Hillman [Podcast]](https://bsmknighterrant.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/teacherlorelogo-1200x685.png)