Parents and adolescents develop different opinions through a variety of ways

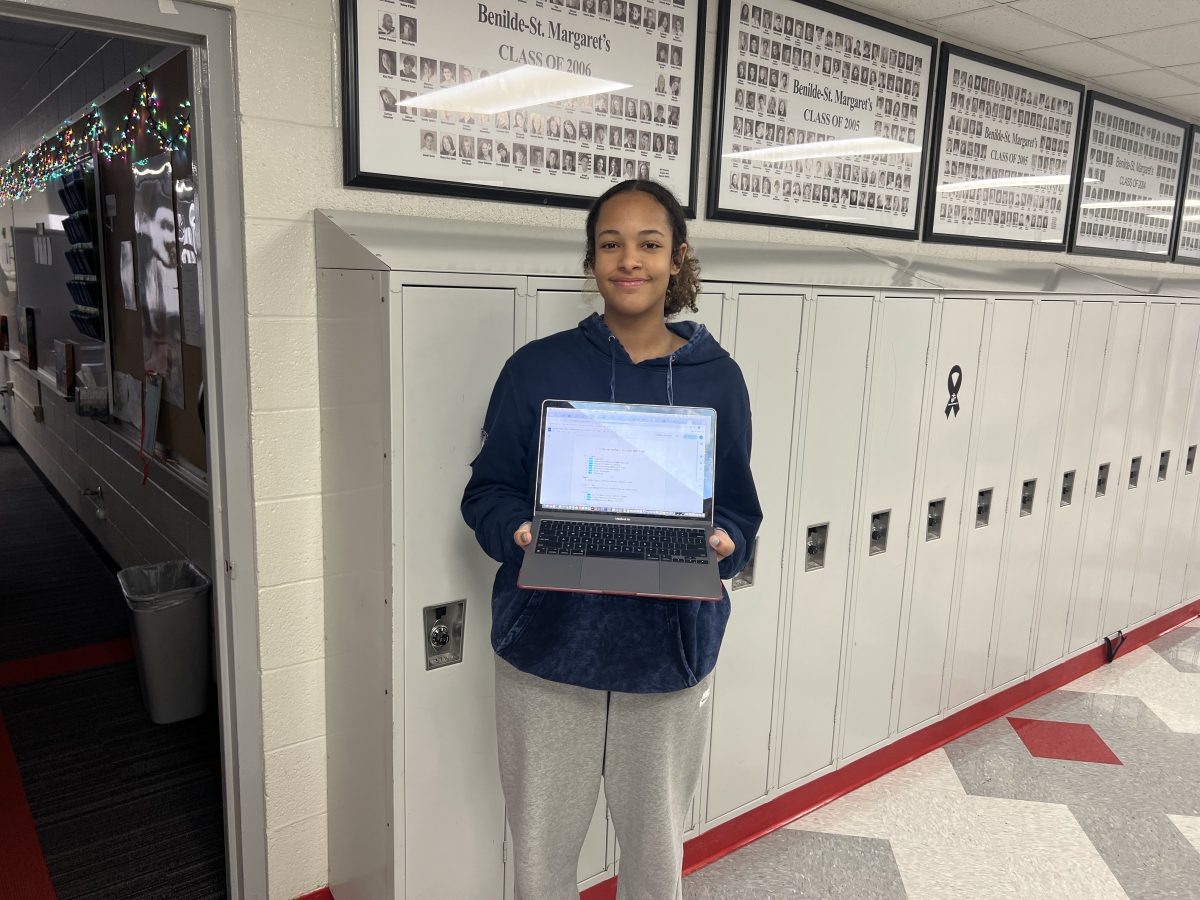

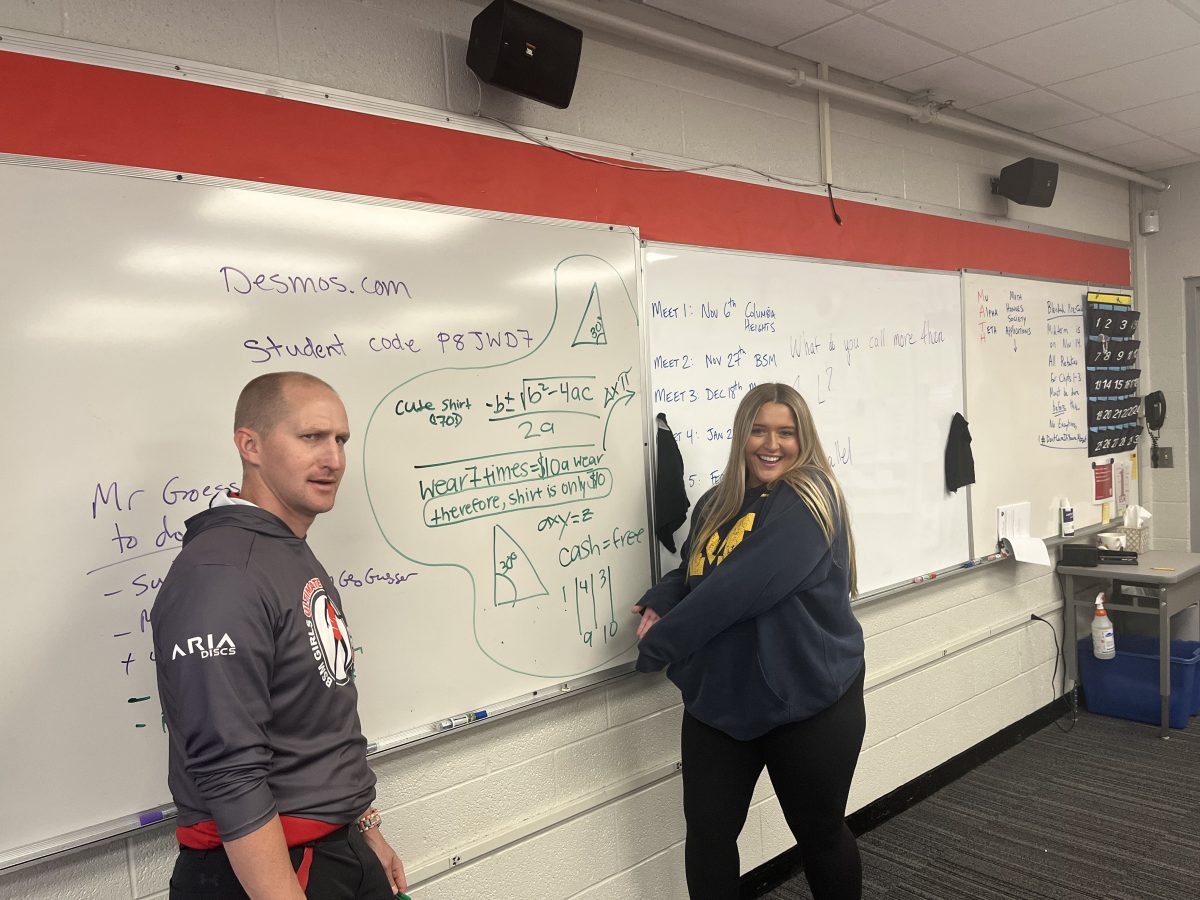

Ms. Maura Brew hopes to encourage free thought in her children, including sophomore Ronan Brew.

In today’s culture, there is so much information circulating on the internet surrounding racial, ethical, and moral dilemmas. Traditionally, children were thought to have shared a similar ideology as their parents on opinions, as they spent a majority of time with their parents growing up and had little exposure to external sources; however, technology is an integral part of the next generation’s development and has significant influence over the opinions of adolescents. As a result, ideas between parents and children can significantly differ, even amidst the traditional misbelief of having the same opinion.

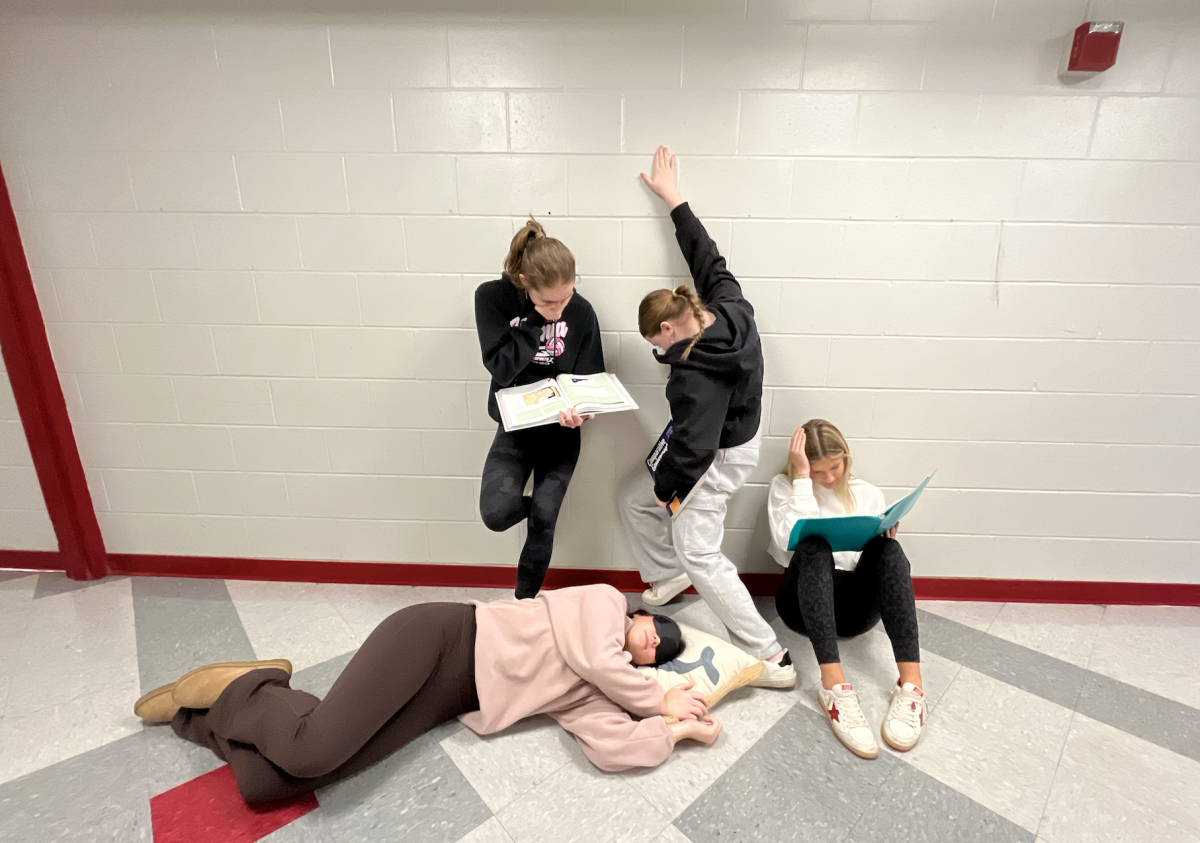

Today, the differences are much smaller than they appear. While there is a trivial misconception that children are grossly radical and rebel from their parents, the truth is quite different. When it comes to forming opinions, there are still similarities between the child and the parent. Children share very similar opinions to parents because they are raised in a climate that develops children to think in a similar way to their parents. Contrastingly, there are still some differences between parents and students, mainly in the form of intensity that they feel for the issue. Generally, parents will be more empathetic and understanding to issues because they have spent more time being exposed to it, while a child may have a more black and white opinion on the topic. “Empathy is something that builds with time. I find that the challenges of the teenage years often mean that empathy is not securely there, but only starting to form” parent and French teacher Ms. Frederique Toft said.

I’d like to think that our willingness to talk about anything made it easier for our kids to see people as we do. — Ms. Megan Kern

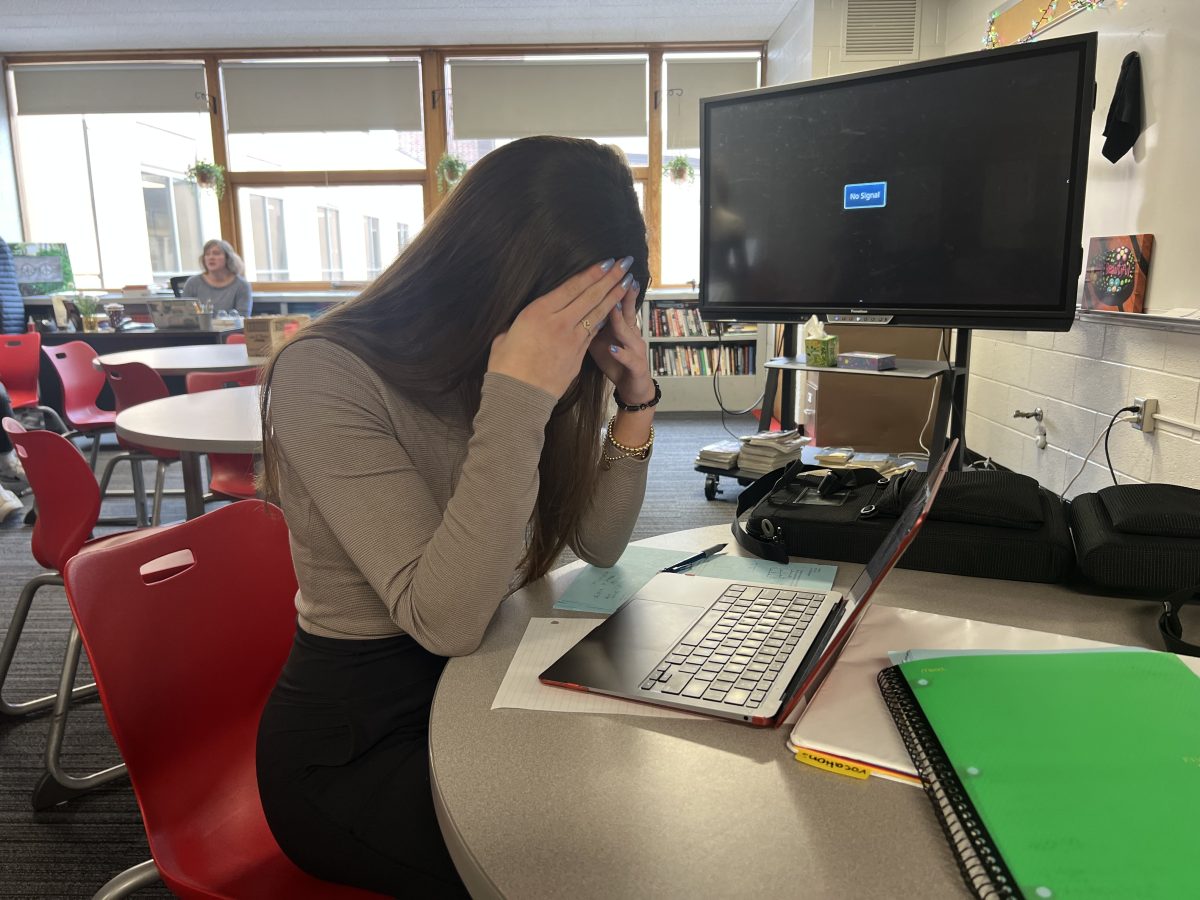

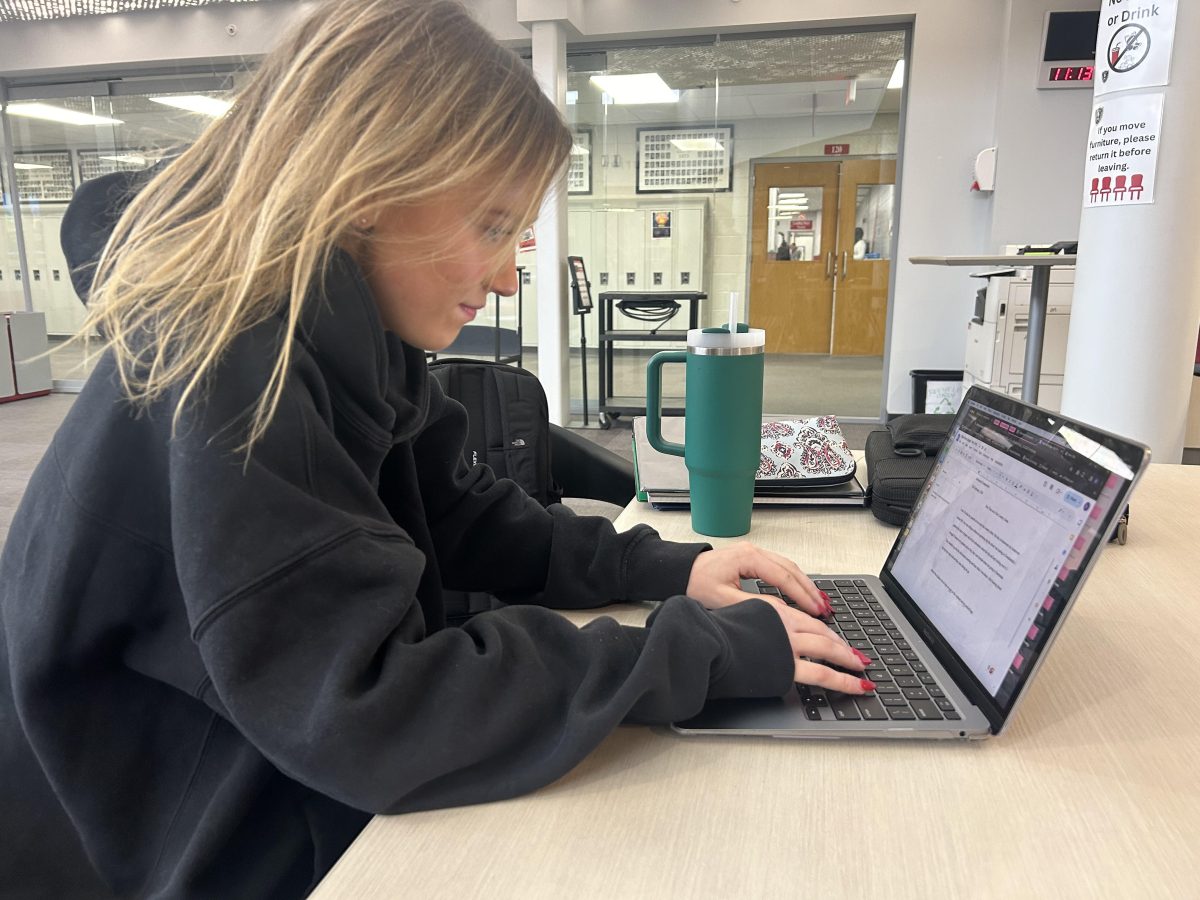

Fostering an environment that breeds healthy, educated, and open-minded conversations is a common theme among parents. Most parents do not want to tell their child explicitly what to think, say, or believe. Rather, they believe that the key to developing their children into aware, ethical, educated, and compassionate citizens of society is to challenge their beliefs and make them think about why they support the side that they do on a certain topic. Instead of almost fearing the parent figures when it comes to controversial issues, most parents lean toward provoking positive conversation and hard thinking on these issues. “I’m constantly having conversations with everyone; classmates, friends, teachers, parents, whoever, as well as reading/listening to news to try and stay up to date on my political standings,” junior Anna Pohlen said. This theme of open mindedness and fostering conversation is something that children and parents can both get behind. It turns homes into a thriving, accepting, and aware environment that develops the next generation into considerate, careful, and curious society members.

In the past, there have been misconceptions about controversial conversations being more black and white, but in today’s culture, parents try to focus on understanding and accepting the gray areas of these hot-button issues. They want their children to do more than look at numbers and statistics, and push them to humanize the situation, talk to people who are deeply invested in the issue, and form educated and considerate opinions. For many parents, this openness in thinking stemmed from their own parents. “Both my husband and I growing up strongly benefitted from parents who were very open minded and who encouraged us to travel. [They] encouraged us to broaden our perspective and I think that that is what we want to imbue in our kids, that same kind of openness and view of the world,” parent and English teacher Ms. Maura Brew said.

The willingness to talk through issues and find ways to overcome challenges teaches children to see beyond numbers, and see people for people. “I’d like to think that our willingness to talk about anything, to discuss hot-button topics (bullying in school, drinking, poverty, gender issues, etc) made it easier for our kids to see people as we do ––as people ––not a label,” parent and history teacher Ms. Megan Kern said.