Shoe drives fail to address poverty in Third World countries

While well-intentioned, shoe drives like the one at BSM don’t actually help people in third-world countries.

October 24, 2016

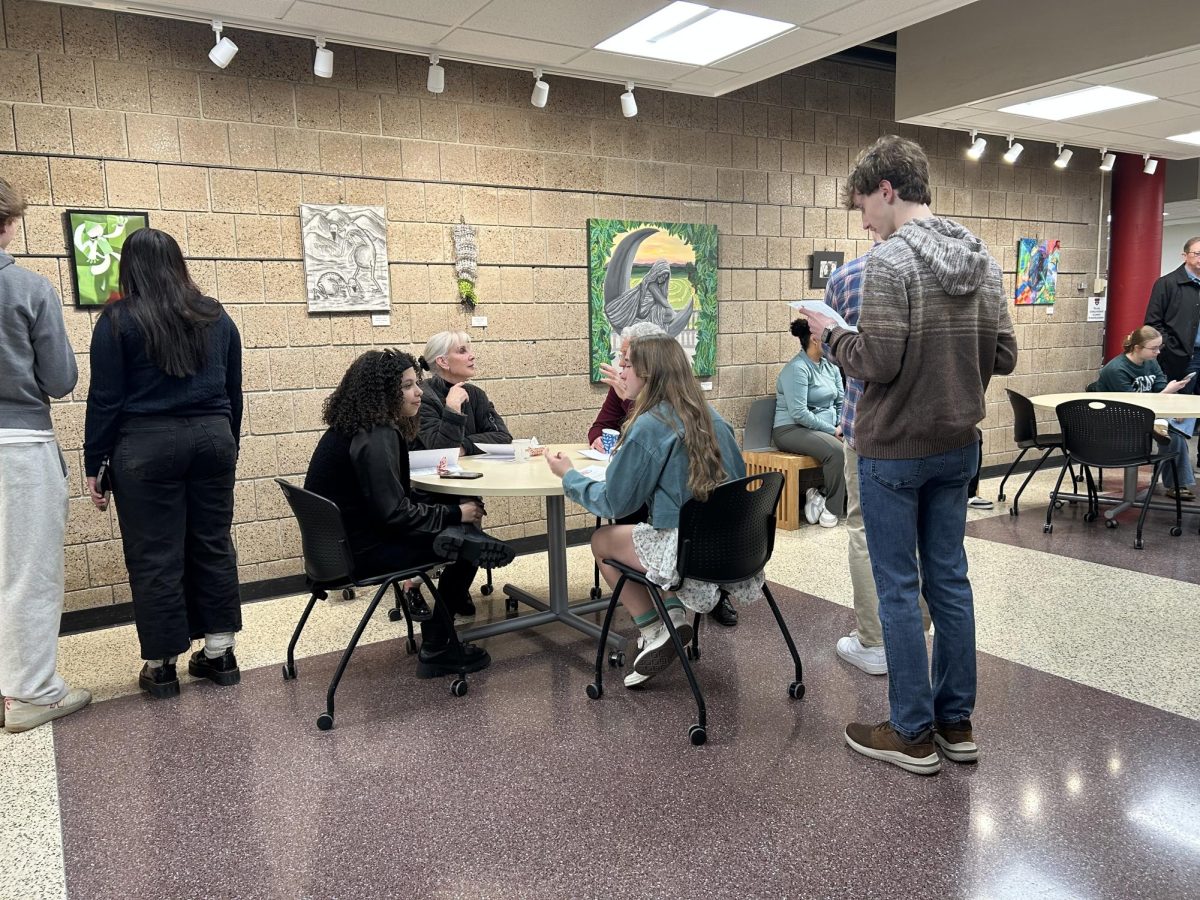

Over three billion people live on less than $2.50 a day. Naturally, given that BSM caters to the upper class in a first-world country, it’s only logical that the BSM community would try to give back to the impoverished. Which is why, from September 23 to October 14, BSM collected shoes to donate to those in third-world countries. While the intentions may have been pure, as a community, the BSM Parent Association should reconsider the use of shoe drives for future charitable endeavours.

Generally, when the idea of poverty in Africa is brought up, most people tend to envision the same thing: naked, malnourished children laying in the dirt begging for water. This is an inaccurate representation of what’s actually happening over in Africa. The images that people use in association with poverty don’t aim to tell the truth; their main goal is to get donations. While Third World countries do have extreme cases of poverty (just like the US), they also have shopping malls, airports, grocery stores, and most other things we have in the US.

The reality is that most people in third-world countries don’t need shoes. They need steady medical care, disability aid, and volunteers to help stimulate their economy, so they don’t have to rely on foreign aid.

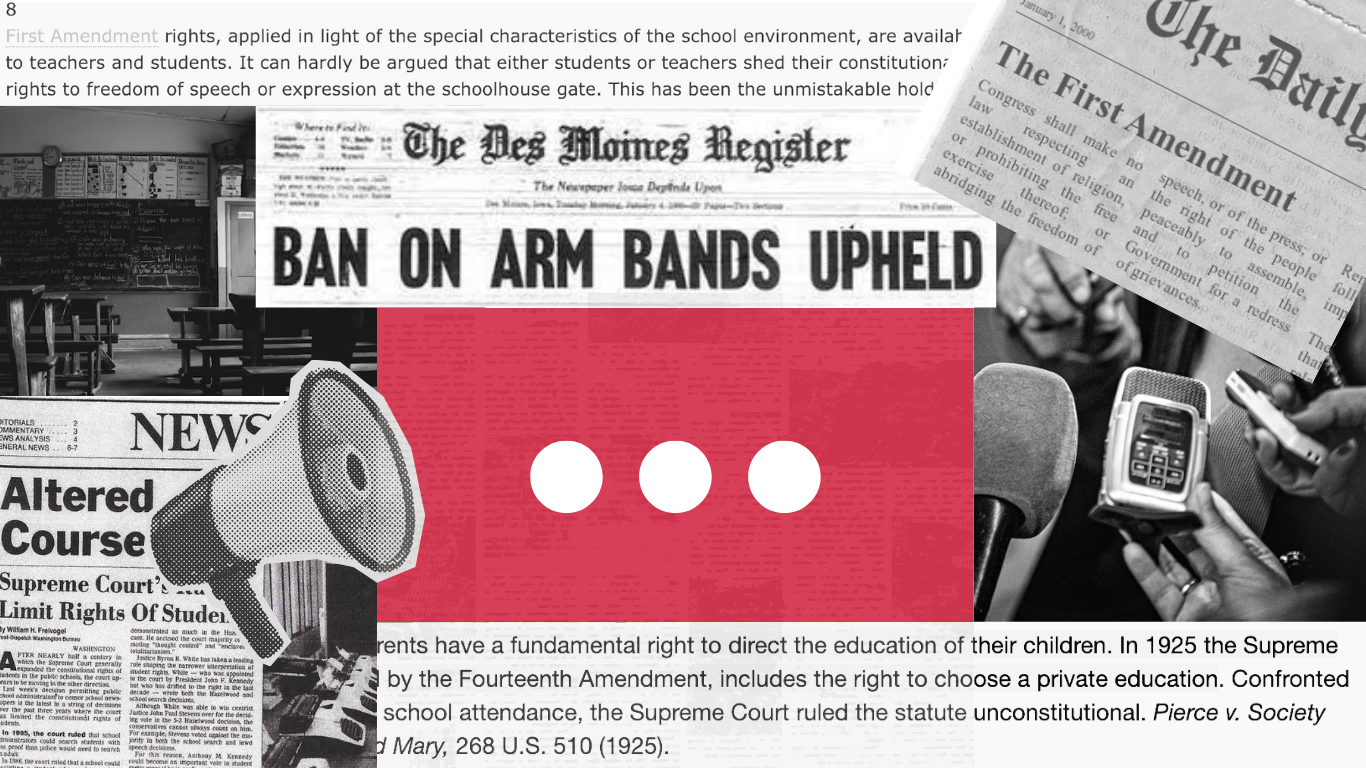

The way Funds2Org—the charity that the BSM Parent Association has partnered with for this drive—works is that they collect shoes, and sell them at a markup to the charity-sponsored ‘hub’ in the country they want to help. The ‘hub’ then distributes the shoes at a markup to local shoe sellers, who then sell the shoes to the people in their town. This means that the people in developing countries aren’t producing their own items, instead, they are reliant on the ‘hubs’ to provide them with with merchandise to fill their shops.

If Funds2Org were to shut down its operations in a country, it is likely that the clothing economy would collapse after receiving that kind of aid for so long. Developing countries have fragile markets, and to take out a charity that spoon-feeds aid would ruin any economic progress the country had made. It’s the classic case of giving a man a fish instead of teaching him how to catch fish.

My proposal to fix this problem is simple: instead of giving shoes, BSM should fund education programs in third-world countries so that the next generation of impoverished youths have a chance to get a basic education. There are 70 million children across the world who can’t get an education, but if BSM bands together and decides to fund a charity like the Campaign for Education, a long-lasting impact will be made and the global economy will see a workforce full of contributing adults who don’t need to rely on foreign aid to keep a sustainable society.

![Teacher Lore: Mr. Hillman [Podcast]](https://bsmknighterrant.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/teacherlorelogo-1200x685.png)

Leslie Wille • Oct 28, 2016 at 4:25 pm

Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.

This is the principle behind Funds2Orgs and was one of the reasons the BSM Parent Association Board chose to partner with this Better Business Bureau-accredited charity. According to the Funds2Orgs’ press release, “Funds2Orgs supports Micro Enterprise in impoverished nations in Haiti, Ghana, Togo, Honduras, Swaziland, Guatemala, Bolivia, Tanzania, Botswana, Benin, Zambia, and Senegal. The shoes are being sent to people who go through a free training program on how to run their own small business selling shoes. They are then given a FREE supply of shoes to get their business going. After the business has been established they can return and purchase the second set of shoes at a very low cost. This enables them to make a huge increase in income, to pay for educational expenses, housing, food, clothing, and even hire employees. Funds2Orgs believes the HAND UP is more beneficial than the HAND OUT, because it teaches people how to be self-sufficient.”

Another reason the Parent Association chose to work with Funds2Orgs was that we were looking for a win-win fundraising opportunity for BSM. Because Funds2Orgs pays for the shoes we collect ($10/bag of 25 pairs), we felt we were combining fundraising with a goodwill gesture. As most know, the Parent Association works diligently doing fundraisers to give back to the BSM community with a year-end monetary gift, which last year amounted to $70,900. This money is raised by parents who devote hours upon hours of their time, successfully planning fundraising events like Knightsbridge, Treasure Hunt, the Shoe Drive, selling gift wrap and HoneyBaked gift cards, recycling cell phones and inkjet cartridges, and sending in Box Tops for Education. The money earned goes to support not only BSM school programs and renovations, but also 8 student scholarships and Random Acts of Kindness, which help BSM families in crisis.

The BSM Parent Association fully embraces the idea that this singular fundraiser does not represent the only answer to impoverishment in underdeveloped countries. Our hope is that Olivia will channel the energy and passion she expresses into creating new opportunities for the BSM community to support all people across the globe, and realize that ALL endeavors to end poverty are worthwhile.

Leslie Wille

Ways & Means Chair

BSM Parent Association