How Does Sexual Assault Impact High School Students?

Above is the National Sexual Assault Hotline. Call if you need help.

“I was confused, in denial; I didn’t want to believe it. It took me a long time to reflect because I didn’t want to think about it. [It was] mentally draining,” an anonymous junior girl at Benilde-St. Margaret’s shared about her experience surviving sexual assault.

Despite constantly telling the offender “no,” she felt pressured to engage in acts she wasn’t comfortable with. “I said no every single time, with reasons to back it up because just saying “no” wasn’t working… But he kept asking; he asked about 20 times… he got angry because I didn’t keep going,” the anonymous junior said.

Students from all over the country have suffered similar experiences. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys in the United States experience sexual abuse as a child. Whether they know it or not, the majority of people are acquainted with someone who has been the victim of sexual assault.

Depression, anxiety and lower self-esteem are just three of countless effects sexual assault can have on an individual. Health teacher Alisa May reveals that a person she knew who had endured sexual assault subsequently pursued toxic relationships, believing it to be normal. “This person is still dealing with people that are not treating her well. Even though we as a family have seen [it], she’s not seeing it,” May said.

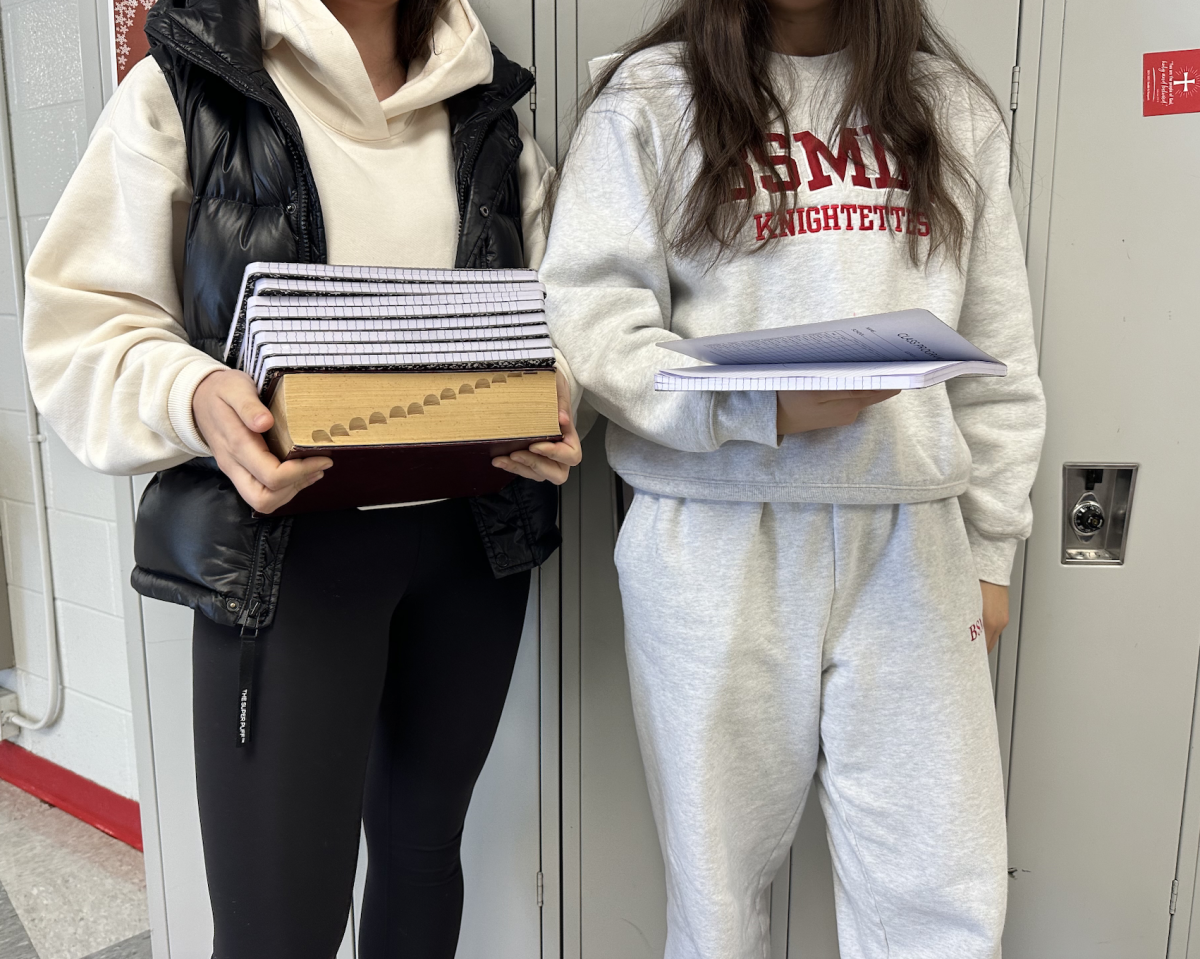

Sonja Benson, a psychologist practicing marriage and family therapy, describes different coping mechanisms that some use in order to bury the traumatic experience. These include using school or other activities as an escape through overachieving. Others may delve into darker places. “That can often involve worse academic achievement up to and including failing, as well as turning to substances to numb the emotional experience and block out memories… Some will actually become promiscuous in an unconscious acting out of a story they believe about their worth and “deserving” to be used/abused sexually,” Benson said.

Guidance & Career Counselor Amanda Anderson has worked with students who have confided their experiences. Anderson noticed a drop in one of the student’s grades due to their inability to continue focusing. This student did not feel like themself, had a hard time pursuing relationships, was frightened to be alone, and had lost confidence. “One of the students I’m thinking of was an incredible singer, and after her assault, she was not able to sing for a few years, as her anxiety prevented her from breathing deeply and making the same sounds that she once was able to make,” Anderson said.

After the experience, many students aren’t vocal about their situation. Anonymous Sophomore girl explained that many students are scared and ashamed. “People are afraid that they’re not going to be believed… But also I think that sometimes [it] probably feels like “I failed. I didn’t protect myself. I could have done something different and I didn’t.”…They are worried because [they] feel like people will look at them differently,” an anonymous sophomore girl said.

Much of this fear stems from the assumption that victims could have been able to change what happened. By questioning the victim about their actions, such as drinking less or dressing more appropriately, society is minimizing their experience and blaming the victim rather than the perpetrator. This isn’t the case, however, when the anonymous sophomore girl’s friend was taken advantage of. “They weren’t drinking. They weren’t doing drugs… And even if they were, I really don’t think it has much to do with that,” the anonymous sophomore said.

Benson further addresses the subject of how society handles cases of sexual assault, especially in terms of the punishment for the perpetrator. “When there are no real consequences for the perpetrator, especially none the victim can actually SEE, it defeats people and causes them to “not bother” when it comes to reporting because the process of reporting is so arduous to the victim,” Benson said.

There are several ways we can help reduce the number of student sexual assault cases and provide the support the students require. May thinks that parents need to talk more about the subject at home, and that we need to teach women how to be assertive. “I think parents at home need to [say] ‘I don’t care who it is. I don’t care if it’s a relative or someone I know. If they’re doing something to you, you need to let me know,’ …[because] who knows what they’re doing? Threatening them? Say no one’s gonna believe you? Brainwashing them to not come forward? So you have that battle, going back and forth of who do I trust and who can I talk to?” May said.

Making sure a victim of sexual assault feels comfortable sharing their story with others – and believing them – is another aspect. “[Talk to] your safe person, whether that’s a friend, a therapist, a parent, an uncle, an aunt, whatever, because you don’t really want to process it alone,” the anonymous junior said.

Students wish for a more proactive approach at BSM. “They don’t bring much awareness to it, but they don’t dismiss it either. I know in situations it has happened they have done something about it. But it’s just not talked about much. I know it is a sensitive topic, but I think awareness-wise it should be [talked about more],” the anonymous junior said.

BSM is working towards being more vocal about the struggle of sexual assault at schools, as they recently featured a safety training program during convocation. Students were divided into gender-based groups in order to discuss material about abuse. “Not Me!™ provides assault prevention and safety classes for all ages: Pre-K through college-aged to professional adults. I think we should have this be an annual program,” Anderson said.

![Teacher Lore: Mr. Hillman [Podcast]](https://bsmknighterrant.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/teacherlorelogo-1200x685.png)