North Minneapolis struggles for sustainable food resources

Despite Minnesota’s image as a progressive, equitable state, neighborhoods in North Minneapolis haven’t seen the same resources when it comes to agricultural accessibility.

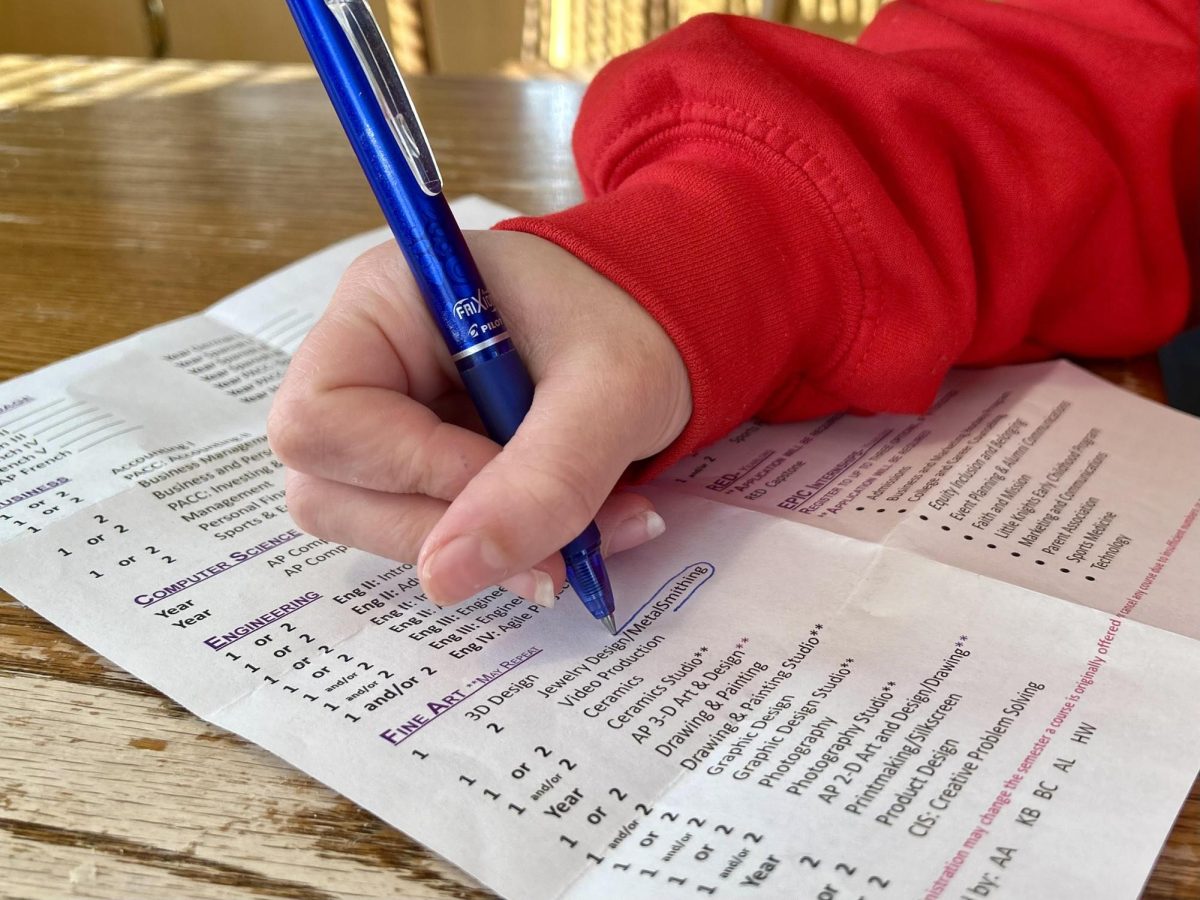

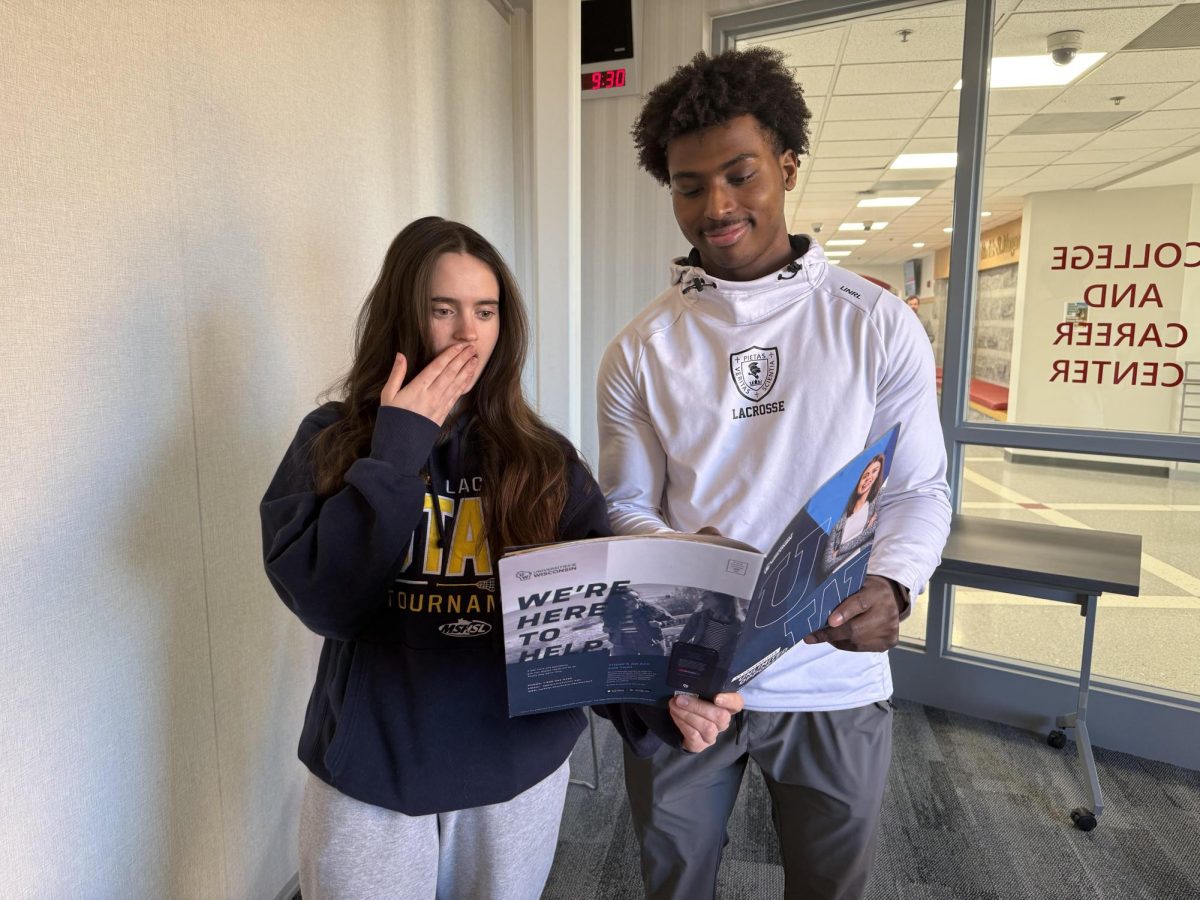

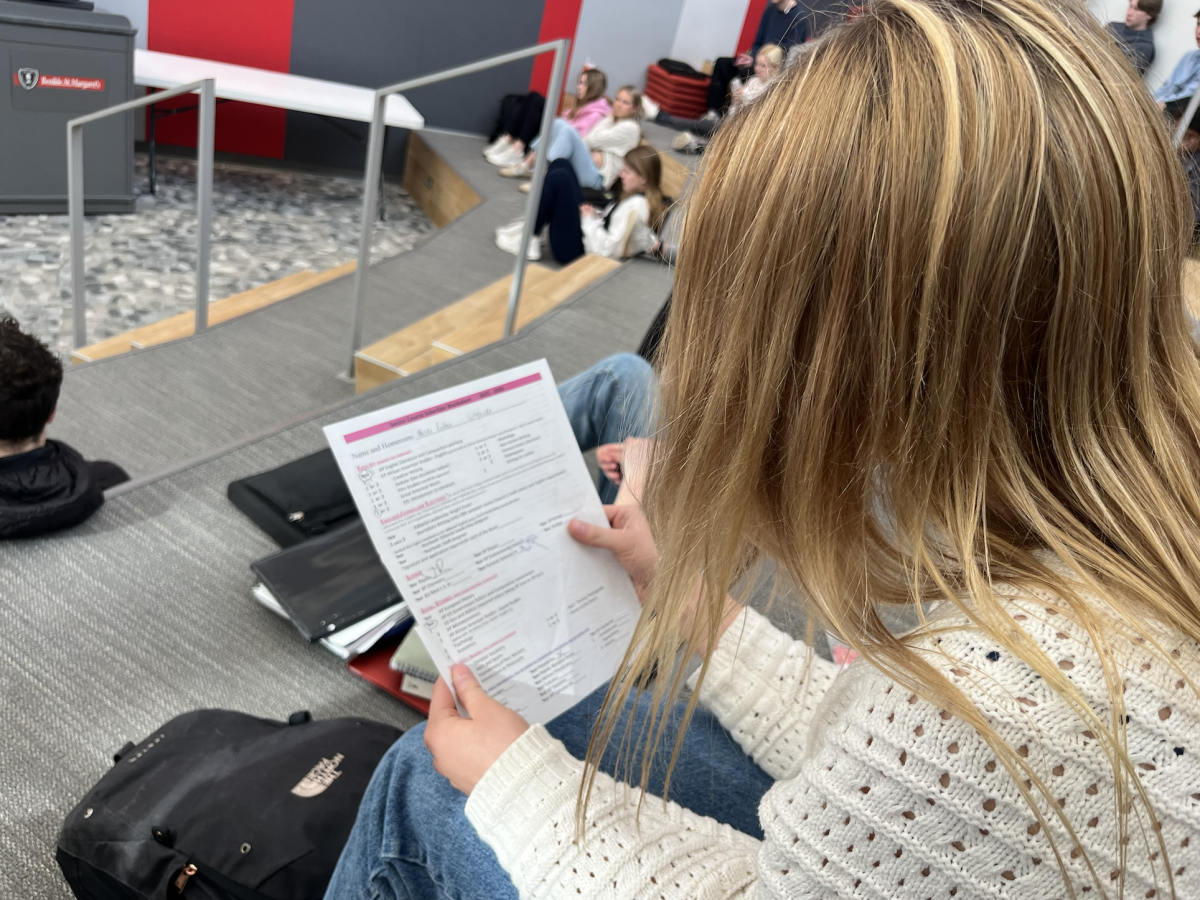

BusyBee delivers boxes of fresh produce to neighborhoods in North Minneapolis. The organization was founded by Peri Warren (’15) in collaboration with seniors Mark Racchini and McKenzie Dunleavy.

As the thirteenth best state for business, the seventh best for economic climate, and a whopping first for overall quality of life, it’s natural to assume that Minnesota is overachieving. However, this isn’t the reality for every community in the state. Looking deeper than surface level rankings, it’s evident that the same economic growth, prosperity, and opportunity isn’t consistently available, especially in pockets of Minneapolis.

What the Forbes’ listings fail to mention is Minnesota’s lack of sustainable food resources. Not only is our agricultural curation an area for improvement for our economy, it’s a growing epidemic: as of April 2016, Minnesota is nationally ranked number seven in worst access to fresh and healthy foods, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Wilder Research. An area with such limited food options is categorized as a ‘food desert’.

In a state so intentionally built on progress, demonstrated through years of championing legislation such as marriage equality, a high-speed rail network (Southwest Light Rail), mental health parity, and issues surrounding education, the intense division between North Minneapolis communities and suburban communities is alarming.

Although the food desert in Minneapolis, specifically in northern areas, is prevalent, the lack of sustainable nutrition heavily correlates to the community’s poverty rates; rates which have been consistently higher compared to rates in Minneapolis as a whole.

When looking more thoroughly into the financial inequities of the city, it’s impossible to gloss over its correlation to race and poverty. For example, the unemployment rates for both Hispanic and White individuals are both nearly 10-14%, while the unemployment rate for African Americans in the area is 28.9%, as of 2012. The poverty rates within North Minneapolis are more prevalent compared to greater Minneapolis as a whole.

For Benilde-St. Margaret’s students, the issue of food deserts hit close to home—especially with 2015 graduate Perri Warren.

“Being a black woman, a lot of my close friends and peers live in urban Minneapolis. And, as someone who has developed a sense of healthy eating, I knew there weren’t a lot of options there,” Warren said.

The emphasis of ‘solving problems that matter’ resonated with students, but it didn’t necessarily inspire all to act. Then-senior Perri Warren was an exception, taking her advocacy work to the next level in founding BusyBee Foods. The student-led initiative is a food delivery service for low income families and individuals in North Minneapolis.

For Warren, her awareness of the issue wasn’t just inspired by a school motto.

As a food delivery service, BusyBee partners with local Minnesota farmers to bring the rural curation of agriculture into the city. “We curate these boxes [of food] on organic, seasonal ability. We want to give produce that’s culturally accurate. We partner with Prodeo academy in North Minneapolis, and they help us cater to culturally specific needs,” Warren said.

Though BusyBee has come a long way in its first couple of years, Warren has higher aspirations than one delivery location. “BusyBee might go national, but for now, we’re focused on having zero food deserts in North Minneapolis,” Warren said.

Within our own community, the initiative to end food deserts is both prevalent and inspiring: the impact that families see with the introduction of fresh fruits and vegetables can completely change the nutritional dynamic and perspective of the family. In fact, Warren has moved back home from Occidental college in California to work on BusyBee and study at the University of Minnesota.

Hopefully, due to the dedication of people like Warren, Minnesota will bring an amazing quality of life to all residents.

![Teacher Lore: Mr. Henderson [Podcast]](https://bsmknighterrant.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/teacherlorelogo-1200x685.png)

Sarah • Nov 2, 2016 at 4:34 pm

This article is fantastic Elizabeth! Great job!