Senior football player Barrett Fitzgerald couldn’t focus. His vision blurred, he felt dizzy, and regular colors turned blue and green—he had a concussion. Sophomore year, during an intense fourth and one play, he hit helmets with another player and blacked out. When he woke up, his vision was off and his head felt different. “I tried to keep playing, but I just couldn’t do it, so I had to come out,” Fitzgerald said.

The next season, during kickoff, he was tackled by an opposing player while running at full speed and went down again. He’d gotten another concussion.

Fitzgerald played during two football seasons with separate, untested, but likely concussions, refusing to tell the trainer, Ms. Kristin Gilbertson, about his suspicions until two months after the end of the football season. Without the time to rest and recover, his symptoms took around five weeks to disappear. He simply would have rather risked further injury than kept from playing football. “I’ve taken good hits, but I’ve never come off the field and been like ‘Kristin I just got hit really hard, and my head’s not right,’” Fitzgerald said.

Stay in or sit out?

Some athletes, like Fitzgerald, regard their beloved sport above their head and brain injury. Waiting an indefinite amount of time to recover is not an option. “You only get 18 guaranteed games of high school football, if that, so I didn’t really want to miss any…I’m fine today. I think that playing through it is absolutely worth it….If you care about what you’re doing it makes it easier to not stop,” Fitzgerald said.

However, most athletes sit out of sports until the concussion symptoms have passed, which could be anywhere from one week to several months. To these athletes, the brief reward and immediate gratification of playing the sport that they love is not worth possible permanent brain damage. Some athletes are more than willing to be cautious with concussions. “I’m more realistic,” senior football captain Mikey Koller said. “It can hurt you in the long run, like in 50 years…we’re so young, and our brains are still developing that you can’t know what the effects are going to be.”

Other students who have a concusion sit out, but do so begrudgingly. In their eyes, some symptoms do not necessarily prove a concussion, but it is better being safe than sorry. “I was really mad and I thought about playing pretty much every day…if it was up to me I would’ve played, but my parents and coaches wouldn’t let me…people are being overly cautious with minor symptoms, but it’s good that we’re realizing more symptoms and we are able to recognize when someone does have a concussion,” said senior lacrosse, hockey, and volleyball player Sara Taffe.

The effect on school

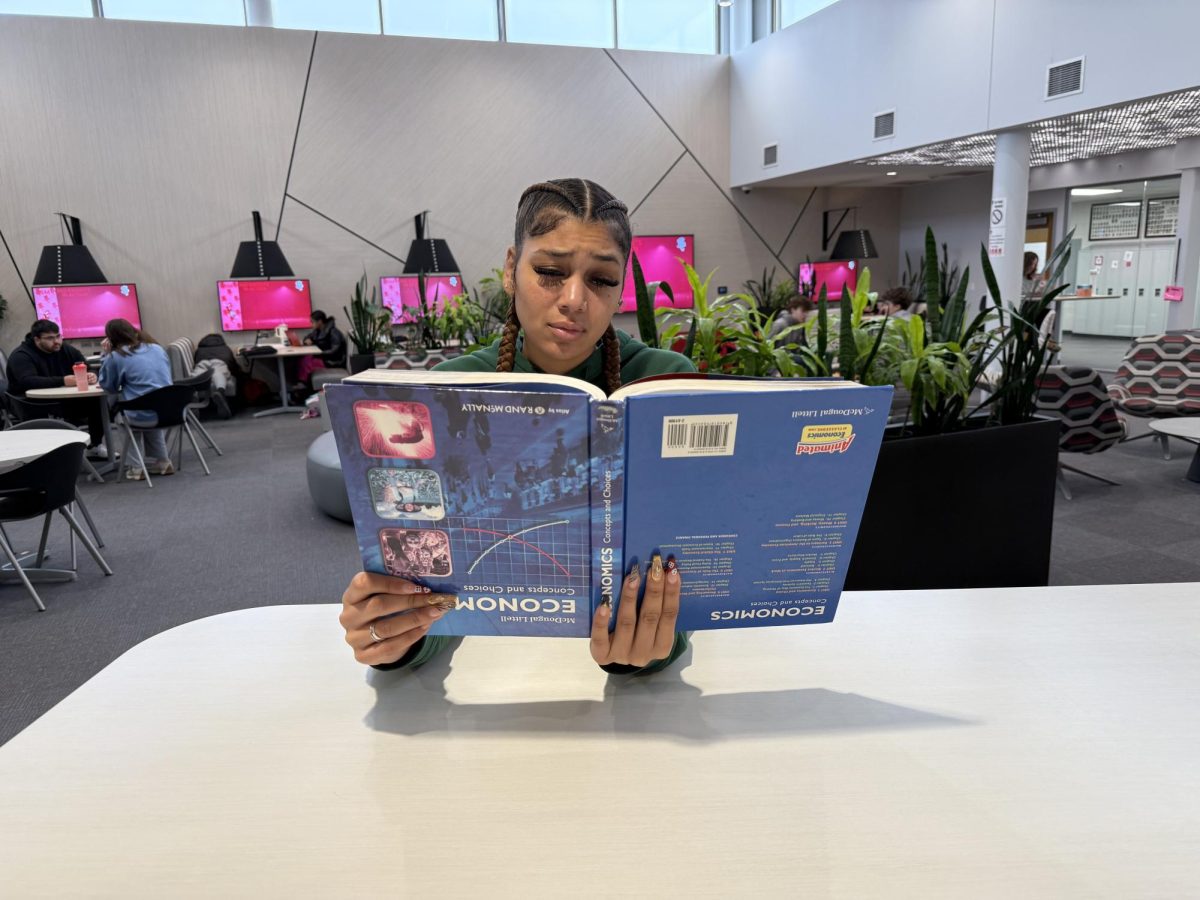

Concussed athletes are not only taken out of their sport, but their symptoms have a direct effect on their schoolwork. Senior Sara Taffe was experiencing concussion symptoms during the last few months of school. “I had a lot of trouble concentrating, I couldn’t pay attention, and I got dizzy if I sat in a class too long; my head would just pound,” Taffe said.

“Fifteen minutes of math homework turned into 30-40 minutes. Working through the problem just gets harder,” Fitzgerald said.

Special training

Coaches and trainers have been educated about how to deal with concussed athletes. They go through training, which teaches them how to look for concussions and differentiate between the minor symptoms from a smaller hit and the more serious indicators. “In the past, most sports regarding hard hits with the ‘he got his bell rung real good attitude,’ but now we are more careful about being sure, without adding too much of a burden on coaches or players either,” varsity soccer coach Mr. Dave Platt said.

“We’re always looking for the symp- toms, drilling the players. We are much more cautious now than we ever have been. We should be overly cautious, and that’s what we should be right now just because of the seriousness of it,” varsity football coach Mr. Michael Swann said.

No matter how the athletes deal with their concussions, most seem to think that concussions are exaggerated. “I think that they’re overdiagnosed because there’s no real way to know that you have one, because all they can base it off of is your symptoms. You can take a CT Scan, but…all you have to do is say that you have a headache, and you could have a concussion,” junior hockey player Sammy Rude said.

“I do think there’s a danger that they are being overdiagnosed, but I think that it’s better to err on the side of caution,” boys’ hockey coach Mr. Ken Pauly said.

![Teacher Lore: Mr. Hillman [Podcast]](https://bsmknighterrant.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/teacherlorelogo-1200x685.png)