“I Don’t Know What That Means”: Students’ Vocabularies Are Dropping

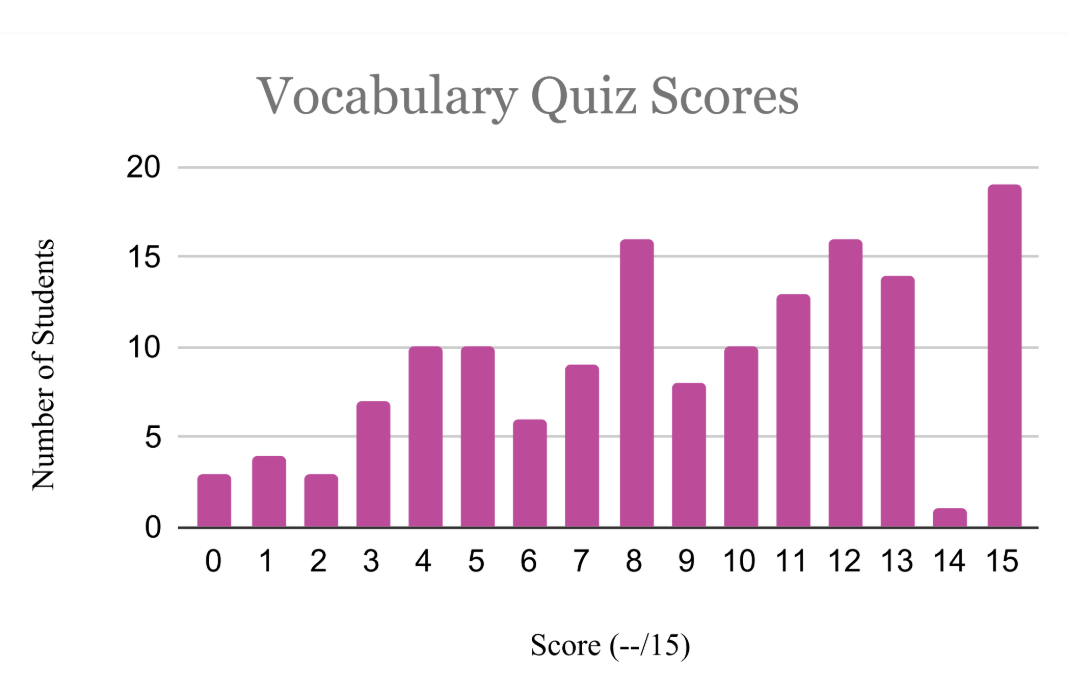

A sample vocabulary quiz was given to BSM high schoolers, attempting to measure the vocabulary decline.

An increase in technology has focused people’s minds on screens and social media—and a sudden decrease in reading has come with these innovations. This decline has affected people of all ages, but most notably, high school and college students today. As these students stopped reading, their vocabularies began to drop.

Compared to years in the past, many teachers have noticed a decline in their students’ vocabularies, especially since the emergence and end of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this doesn’t mean that the vocabulary decline started because of the pandemic—this is only when educators began to take notice of the problem. BSM reading specialist Nancy Maistrovich agrees that the problem is likely long-term and has increased over time. “I think that students have really been struggling with vocabulary for a while. When I taught English [I found] kids struggling… It seems to be that there’s a decline in reading for fun, or in kids reading outside of school,” Maistrovich said.

In an attempt to measure the decline, the Knight Errant surveyed over 150 students and gave each a sample vocabulary quiz. This quiz included 15 of the most commonly found words on the SAT, words high schoolers are expected to know. Results came in from classes in all different grades; the scores ranged from 0/15 to 15/15, averaging 8.97/15. The results of this quiz made it clear that there was indeed some sort of decline.

This decline in students’ vocabulary is especially prevalent when looking at reading and writing skills. A lower vocabulary can result in a longer time to read something, particularly if the skill of reading isn’t practiced often. Students may also struggle to write if they don’t have the vocabulary to fully express their thoughts—and this struggle can lead to subpar writing. “There are some words I’ve seen that seniors don’t know. They are often words [the seniors] should know, and that’s kind of disconcerting. Also, the fact that they can’t figure out the gist of the word from the context clues is discouraging as well,” English teacher Anne Marie Dominguez said.

In a survey sent out by the Knight Errant, 76.3% of students surveyed reported if they came across a word they didn’t know while reading, they would either skip over the word and pretend it didn’t exist or attempt to use context clues to figure it out, rather than looking up the word or asking someone what it means. While context clues can be helpful and often lead to the meaning of a word, students may incorrectly interpret context clues and glean an inaccurate definition of a word. The best solution, in this case, is to look up a word to learn the correct meaning.

There has not just been a decline in standard vocabulary—everyday words students are expected to know—but also scholarly vocabulary, which shows up in readings and textbooks. Many history classes require students to read and take notes from a textbook, and this can be challenging to do if there are many unfamiliar words.

“I see [evidence of this decline] most often on a test day when [students] are looking at questions and are unsure what the question is asking because they don’t know what the standard or scholarly vocabulary word means. I get asked what static means a lot, along with other words I wasn’t asked about 10 years ago,” social studies teacher Cherie Vroman said.

Nevertheless, this isn’t to say that all students have no vocabulary. In fact, many students might know numerous words but don’t necessarily use them. “Sometimes I find that students have more access to vocabulary words than they think, but they get so locked into using such a finite amount [of words] that they just don’t think to use others,” Dominguez said.

This desire to only write using the same words can result from seeing the same words constantly used online. As technological innovations were introduced into society, the use of cell phones increased dramatically, which contributed to a decline in reading. “That [increased use of technology] opened a whole world of people, of students, to be entertained by what they see on their phone, as opposed to reading a book,” Dominguez said.

While reading trends are generally declining, bumps in reading have occurred as popular book series are published or revisited on social media, such as popular “BookTok” books like The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller. When these books are brought up repeatedly, more people are encouraged to read, and this reading can slightly increase the vocabulary of these readers. Nonetheless, these people are only a minority; the vocabulary scores of U.S. students have been steadily declining since 2009.

One of the most effective ways to increase these vocabulary scores is reading. Typically, someone needs to see a word eight to ten times before they feel comfortable using it as part of their everyday vocabulary—and reading is an essential tool in exposing students to new words. “Students need multiple exposures to really have a word in their vocabulary. So I think the easiest way to do that is to read often and see words repeated. I know it’s hard for students sometimes and some don’t like reading. However, it’s the easiest and most effective way to grow your vocabulary,” Maistrovich said.

Along with reading, it’s important to use new words in conversation. Seeing how words are used in context is crucial and can lead to a greater understanding of a word, which in turn, can lead to an increase in vocabulary. To help with this exposure and context, teachers can use elevated words when communicating with their students. “If teachers and superiors use more advanced vocab words in their daily life and daily teaching, we would definitely be utilizing them more in our daily life,” sophomore Arwen Patell said.

BSM has tried to encourage reading by implementing “Reading Wednesdays,” where students are required to read in homeroom for 20 minutes. While this is a good strategy, it’s not always enforced and not everyone reads. “It’s rare that someone has a book they’re reading. They grab something off the shelf and they read for 10 minutes, or they pretend to read for 10 minutes, and then throw the book back. I’ve got only a handful of kids who come with a book they are actually reading,” Vroman said.

This decline in high school students’ vocabulary then begs another question: If a lack of vocabulary greatly impacts high school students, what happens when they reach college? Are college students also affected in the same way?

Geoff Herbach is a Professor of Creative Writing at Minnesota State University Mankato and a young adult author. He has noticed not all of his students come into college with the same level of vocabulary that some of his students have had in the past. This decline in vocabulary can then make it difficult for a student to keep up in a class. “If [students] don’t have the vocabulary to deal with college-level reading, it becomes an incredible struggle to get through an article or to get through a book,” Herbach said.

Students are also reading more on screens, which is fundamentally different than reading a paper book. “It means that they’re encountering, in some ways, more words than people ever would have been 20 years ago, but there’s not as much of a diversity in those words,” Caroline Melly, Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Sherrerd Center for Teaching and Learning at Smith College, said.

Many students prefer this approach because it means they don’t have to try to understand more difficult words. “They’d rather have a straightforward summary of the text… That’s what the internet does for us… I think [students] struggle a little more when the voice of the text is a little different, or when it’s more poetic, or when the vocabulary is more ornate,” Melly said.

Much of this online reading is brief articles that require shorter attention spans and less effort to understand. Many people wish to direct their attention to something for only a short time, resulting in a decline in reading long texts. “I think that we’re a more visual culture rather than a reading culture now because people look at stuff on their phones rather than reading things in magazines and books,” Herbach said.

Some students come into college not having finished a single book before because either they haven’t read books assigned to them in high school, or they weren’t assigned a full book in high school. Furthermore, some students don’t have the writing and revising skills many professors expect them to have; this lack of skill can lead to challenges in the classroom.

“I would say we are at a moment of dramatic transformation in higher education for a lot of reasons, but one of them is certainly because students are coming less prepared academically than they used to be, and also differently prepared than they used to be. Our students are just as smart as they ever were and have just as much promise and capacity as they ever did, but what they come with looks really different, and when they come there’s more of a friction between what faculty are expecting and wanting students to be able to do and what they can actually do,” Melly said.

It’s a lot to ask teachers to tackle these problems independently. Challenges with reading and writing are present not only in college but also in high school and middle school. Teachers will do their best to help their students, but some of the responsibility also falls to the students to take charge of their own learning. “I also feel like it’s not just on teachers, but on parents as well. If they want their kids to process stuff, they have to read to them when they’re little. They should encourage reading during the day and before bed. I think it will take a commitment from both parents and teachers,” Herbach said.

This problem is also difficult to solve because vocabularies are constantly changing—it is hard to measure something frequently changing and it is hard to say for sure how much the average person’s vocabulary has declined. “Language is changing, and our needs for it and our expectations of it are changing, really fast. The difference between [now and the past] is so big; it didn’t used to be that change was happening that fast,” Melly said.

Though it may be slight, many teachers and students alike have noticed a decline in the vocabulary of their students and classmates, and it’s clear something is going on. Whether or not it’s a problem that will continue remains to be seen, but as for now, declining vocabularies are very present in schools.

Regardless of level of education, reading can positively impact everyone and increase ever declining vocabularies. There is no easy and perfect solution to this problem, especially as types of education differ, but reading is a good start. “If you can get up to an hour where you can read for 45 minutes to an hour every day, you will notice a difference in your vocabulary,” Dominguez said.

Elizabeth Mitlyng • Nov 21, 2024 at 4:58 pm

It’s clear how much effort and hard work you put into this article, Charlotte. I applaud you for interviewing a multitude of people, -especially college professors- including a video and graphics, incorporating research links, making a vocabulary test, and everything else. Thank you for showing everyone who reads the Knight Errant what is possible. Your diligence(hope I used that word right!) doesn’t go unnoticed.