Eighteen-year-olds have been eligible to vote since 1971 when the 26th Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified. As high school students, many of our peers will turn eighteen before we graduate, able to take on the civic duty of voting. However, the Knight Errant Editorial Staff would argue that Benilde-St. Margaret’s has left them largely unprepared. Considering how vital participation is to our democracy, Benilde-St. Margaret’s has a duty to emphasize the importance of voting and civic responsibility in a nonpartisan, educational way–not only do students deserve it, but our country does too.

Although the 2024 presidential election is nearing, there’s a noticeable reluctance to discuss anything pertaining to the election or politics as a whole at BSM, even in a neutral, educational context. It’s understandable—politics has become a taboo subject and can be extremely controversial. Yet this reluctance has extended to anything even considered to be in the proximity of politics, whether that’s discussing how to register to vote or why it’s important to stay informed. To be clear, the issue isn’t that partisan politics aren’t discussed—the issue is that unbiased information about politics and civic engagement is decisively avoided, even in an educational context.

In a voluntary Knight Errant survey, 42.9% of respondents stated that they believe there is a stigma around discussing politics in a nonpartisan, educational context at school. This stigma haunts teachers as well as students. “I think that as a teacher [what] you are trying very, very hard to avoid is to appear that you’re putting your finger on the scale of taking one side over the other… when we look at the divisiveness in [our] culture, whether it’s over race issues, LGBTQ issues…I think the stigma is just to stay away from [those political issues],” social studies and government teacher Ken Pauly said.

This stigma does the BSM community a disservice: rather than steering clear of just partisan politics and opinions, we avoid discussing anything related to politics. Students will be able to vote regardless—all this does is deprive them of the educational context and tools needed to be a good citizen. Furthermore, the goal of education is to teach students to think critically. Students should not only know the facts but be able to decipher opinions from reality, as well as interpret information to come to their own conclusions. By tip-toeing around the discussion of nonpartisan politics, the BSM community is denying students the basic knowledge needed to be an analytical, informed citizen: a voter. “One thing I’ve tried to emphasize is ‘let’s be analytical rather than personal’ and that’s easier said than done…So [for] me, [it’s important to] inform people first… If you’ve never read the Constitution, if you don’t know what the Constitution is, let’s start there. It doesn’t mean we can’t elevate it to other areas, but I just find [there’s this] fundamental ignorance of just some basic ideas,” Pauly said.

That’s exactly why a focus on civics education, not just in the classroom but as a community, is vital for preparing students to be good citizens. Currently, some seniors take Government or AP Government, where they discuss some of these topics. However, many seniors aren’t taking any civics classes; they have already completed their history requirement. To address this, BSM is now transitioning to requiring civics classes for all high schoolers, which is an important step toward achieving this goal. In fact, as the Brookings Institute highlighted in a 2020 article, research may suggest a correlation between quality civics education and higher student civic engagement. Pauly would argue the same. “That kind of gets back to even the original philosophy of education [and] the classic quote… from Ben Franklin… He said ‘We have a Republic if you can keep it.’ If you can keep it. [I]t was written for this sort of society; this sort of Republic doesn’t work without a large, educated [society]…And so if that’s the case, then [civics education is] certainly something we should be doing in school,” Pauly said.

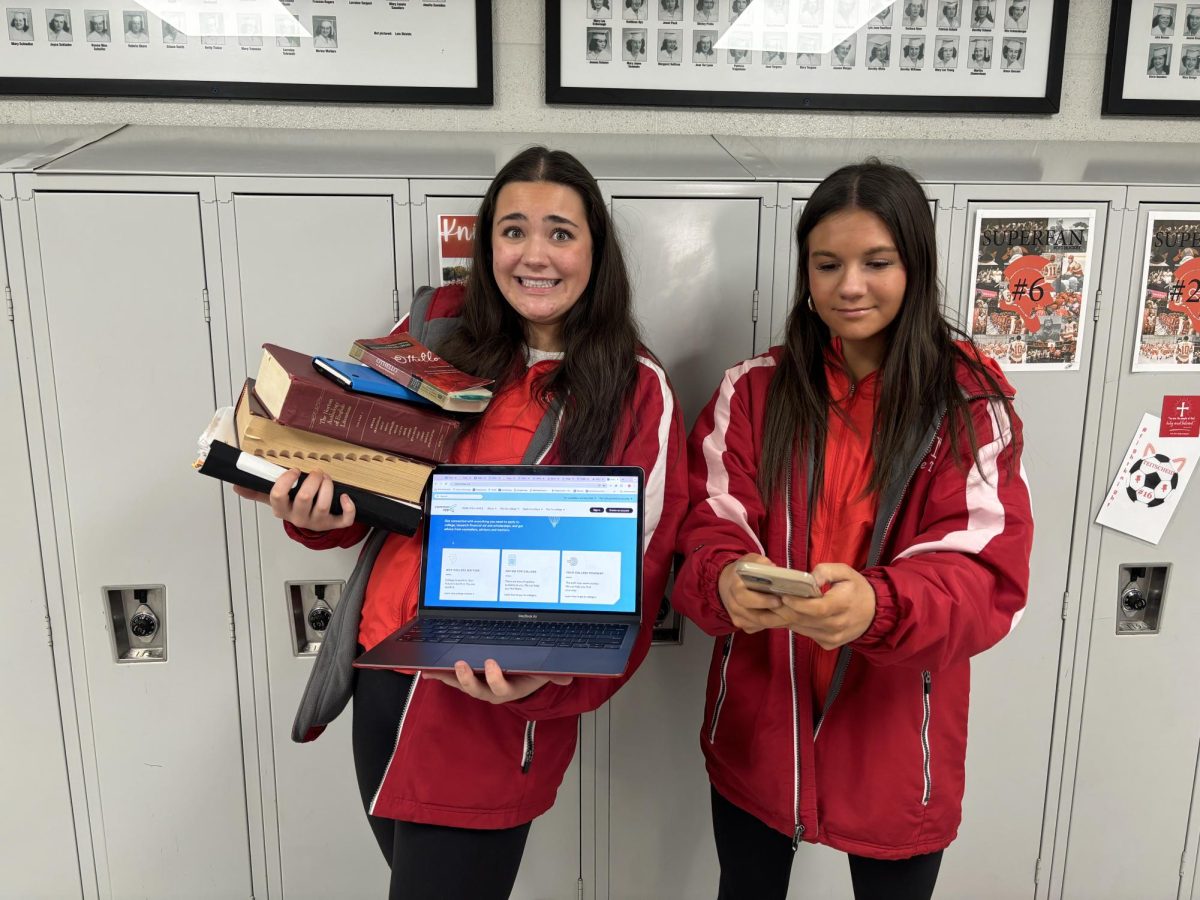

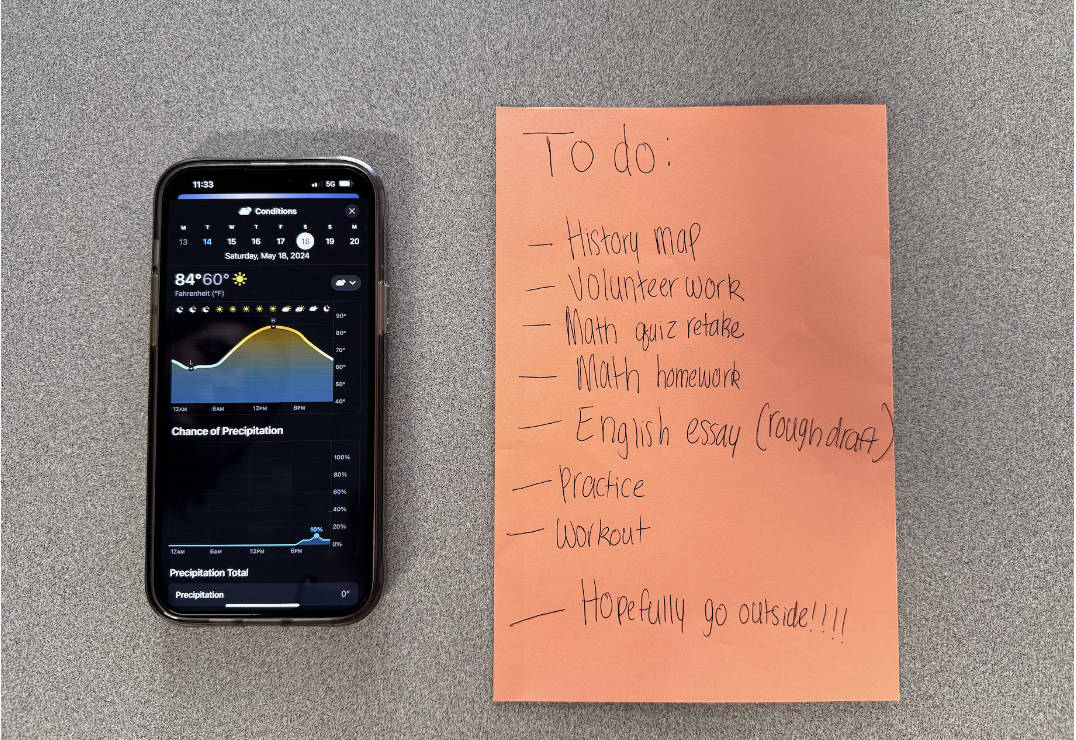

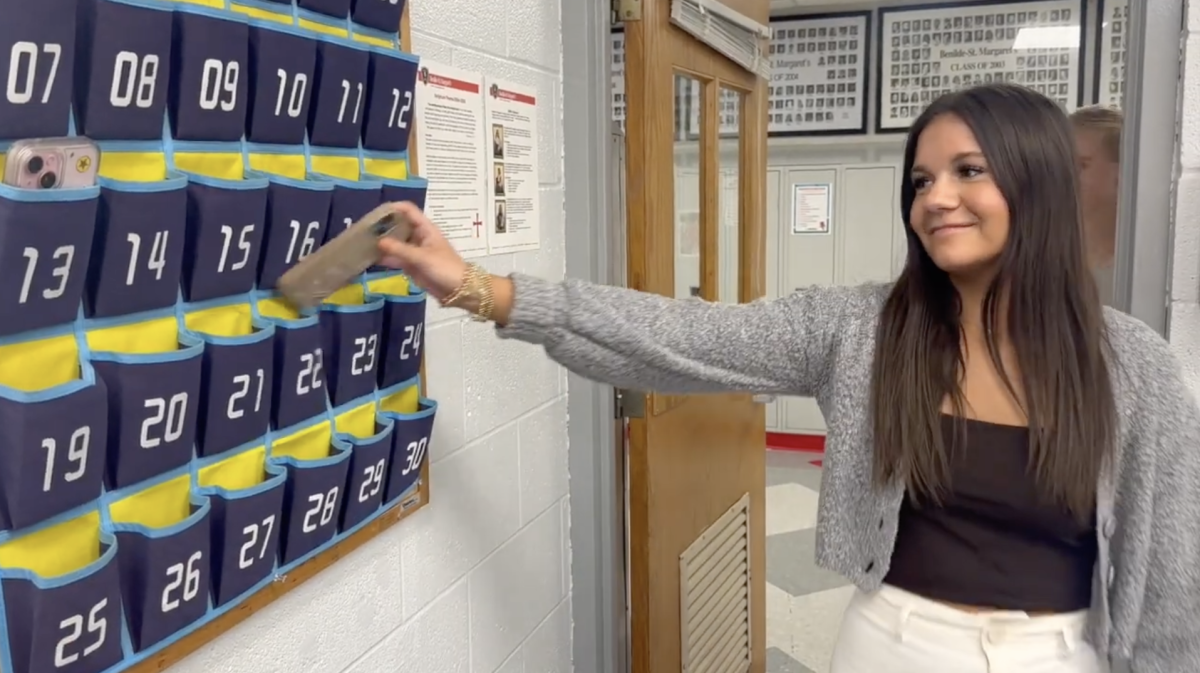

However, to address the stigma about voting and nonpartisan political information, BSM needs to take action on a cultural level. Not only could we decrease the stigma around politics by facilitating respectful spaces to learn and engage with educational information about our government, but BSM could also do more to provide specific information about voting as a process. It’s crucial to ensure younger Americans are truly showing up in the democratic process. A FiveThirtyEight analysis conducted around the 2020 election cycle found that young people are more likely to experience voting barriers. To combat this, BSM could educate students on nonpartisan, state-provided resources, including the online tools that allow Minnesotans to register to vote and check their polling places. Encouraging students to participate in our democratic process, armed with the knowledge of its importance and mechanics, is critical.