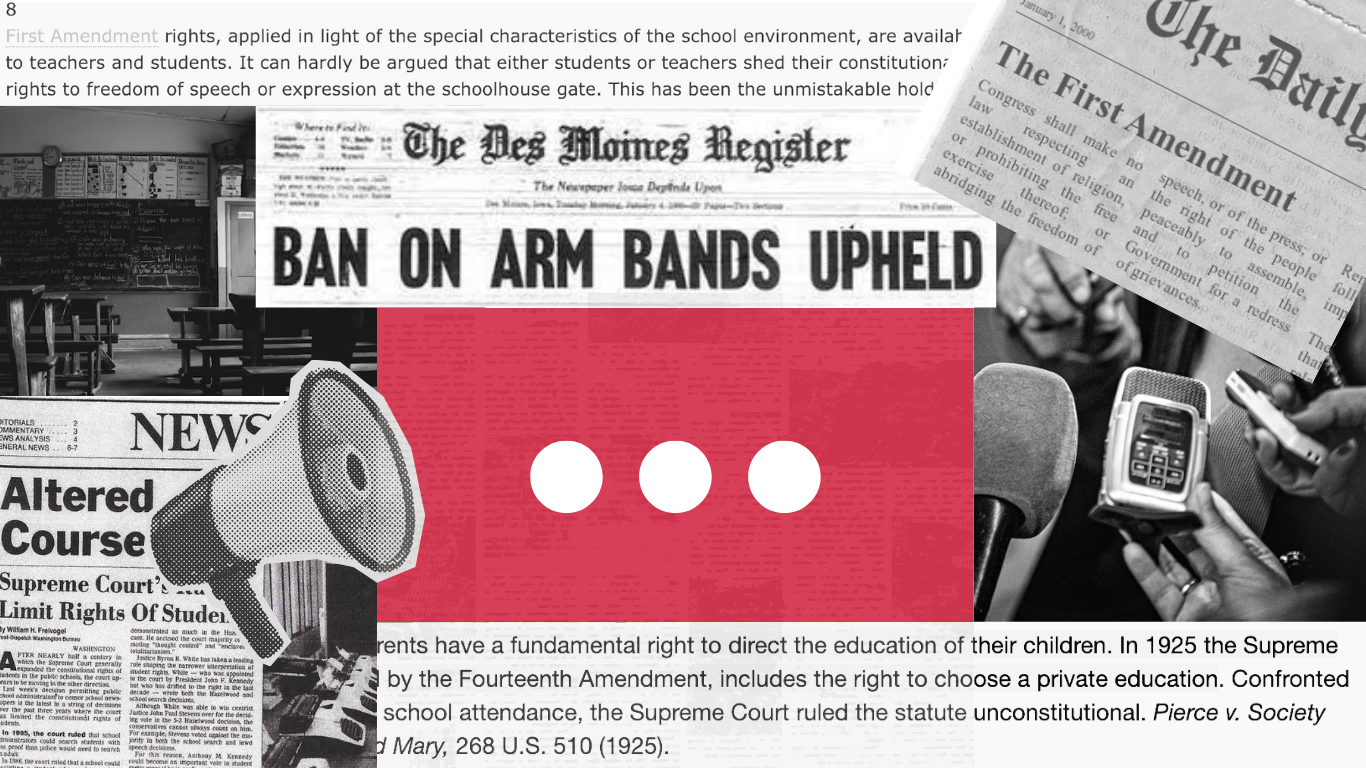

If you are an American, you have First Amendment rights. These include freedom of religion, freedom of assembly, freedom of speech, the right to petition the government for redress, and the right to be free from government establishment of religion. However, the First Amendment has limitations, especially regarding free speech. Certain types of speech are not protected, and you are only protected from being censored or silenced by the government. For public schools, this means that speech is relatively unfettered. There are some cases in which the First Amendment doesn’t apply in public schools, but these are few and far between and require stringent legal thresholds to be met.

In private schools, this is different. Private schools are not required to abide by the same First Amendment rights as public schools, because they don’t receive federal funding. While students’ rights will vary from school to school, especially depending on state laws, the fact remains that private schools are largely legally capable of censoring their students.

However, most private school students are not aware of how their rights differ from those in public schools. In a Knight Errant survey, around 89% of students believed that the First Amendment either fully or partially applies within private schools. Many were unaware that the First Amendment applies only to government censorship. Common survey responses included an assertion that the First Amendment applies in every space.

Censorship also applies to the right to protest and the right to free speech in other contexts than student journalism. Although Justice Fortas, writing for the court in Tinker V. Des Moines, said “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” this is exactly the situation at many private schools. Rather than shedding our constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate, we are shedding them at the “sign here” line on a contract. Tinker applies only to public schools, and so do all the other SCOTUS precedents that affirm students’ First Amendment rights. “In private schools, there’s not that First Amendment protection. We don’t get to benefit from the Supreme Court’s decisions where they’re mulling over what all of this means in the school context for private schools,” said Jonathan Gaston-Falk, a staff attorney with the Student Press Law Center.

However, according to additional resources from the Student Press Law Center, a private school student may have some defenses. Firstly, they can appeal to the school’s morality using the argument that just because private schools can censor student journalism or otherwise stop free speech doesn’t mean they should. “I think [free restraint in journalism] is not just a benefit. That’s essential. Because the job of journalists, whether students or professionals, is to observe and record and document what’s happening and sometimes those stories are not always pleasant, but as long as student journalists are abiding by the ethics set out by the National Student Press Association, then there should be no problem,” English teacher and Knight Errant adviser Tiffany Joseph said.

Many private schools do subscribe to this argument, even if they don’t have specific policies that protect student journalism. “Journalism has always been a part of BSM, and students have had the opportunity to write about the things that matter to them. The only time we try to intervene as an administration is if what is being written about could potentially harm another student or other member of our community,” BSM Senior High Principal Stephanie Nitchals said in an email interview.

Secondly, students can take a look at their Student Handbook, Code of Conduct, or other school rules. Many schools adopt policies that protect students’ free speech, and if that policy is specific enough, it may be possible that courts could consider it a legal contract. The Student Press Law Center goes on to state that several courts have found that the provision of these school policy documents (like a student handbook), along with an admission offer from the school, an acceptance of said offer, and payment of tuition together may constitute a contractual relationship. As a result, if the school fails to abide by its own policies that protect free speech, it can potentially be held in breach of contract, assuming that certain legal standards are met.

“We have to be a little bit more creative because we can’t rely on the First Amendment in private school. So instead, we have to rely on some of the language that has hopefully already been considered and passed by those boards [of directors]. And so once you’re able to find those policies, you can also look for recruitment documentation. How did you wind up coming to this private school in the first place? There are some quasi-contract arguments, you know, the idea of you giving tuition in exchange for your schooling,” Gaston-Falk said.

However, according to an article from the Mitchell Hamline Law Review, the effectiveness of contract law as a means to legal redress for speech suppression in a private school remains uncertain. Minnesota courts have adopted more stringent thresholds that must be met for contract law to work in these situations. In addition, schools usually shy away from potential litigation, although this tends to result in compromise.

“It’s not something that we’ve seen a lot of. Typically, just by having an administrator confront the idea that this could be [a] quasi-contract [situation], that typically makes a lot of these matters go away or there’s some sort of middle-ground settlement. Like I said before, administrators we’ve found have wanted to compromise and establish some sort of middle ground where there is that expectation or that expression, but tempered by the concerns of that administrator,” Gaston-Falk said.

Fortunately, some states have implemented policies to protect free expression for private school students. For example, California’s private school students enjoy unique protections under the Leonard Law, which extends the First Amendment to all private colleges, universities, and high schools. According to the Stanford Office of Community Standards, this means that only unprotected speech can be subject to discipline under the Leonard Law.

Unprotected speech is described as extremely serious and injurious speech to the point that it meets a legal threshold. This may include sexual harassment, race-based harassment, obscenity, fighting words, incitement of imminent lawless action, true threat, and defamation. There are a variety of high legal standards that must be met for speech in any of those categories to be considered “unprotected”, and as a result, most speech would remain protected by the Leonard Law.

However, California is one of the only states with these kinds of free expression protections for private school students. New Voices bills, which protect the First Amendment rights of student journalists, have been passed in seventeen states, but these apply to public schools, not private schools.

Overall, your rights as a private school student will differ depending on your state and school. Generally speaking, however, private schools are not legally compelled to follow the same First Amendment regulations that public schools do. Some schools will voluntarily adopt policies to protect student speech, but not all. Whether or not you “shed your constitutional rights at the schoolhouse door” depends on a variety of factors, ultimately meaning that the First Amendment as it exists in popular perception doesn’t apply at private schools.