Behind the Scenes: Science Curriculum Development

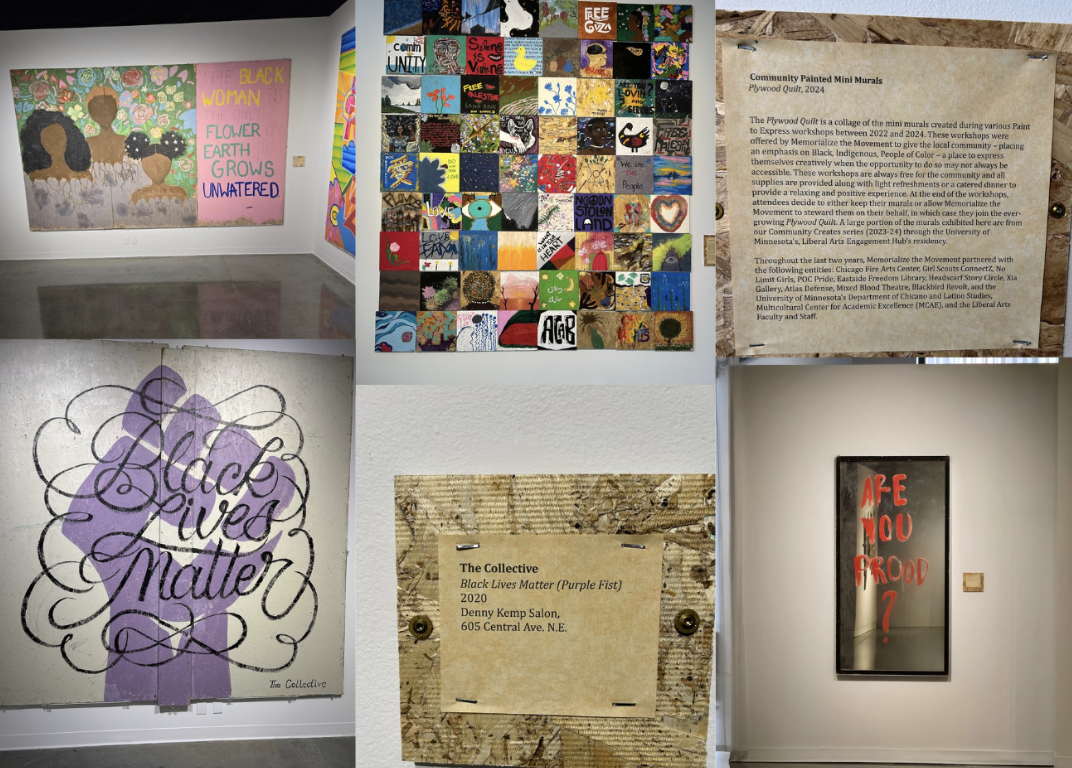

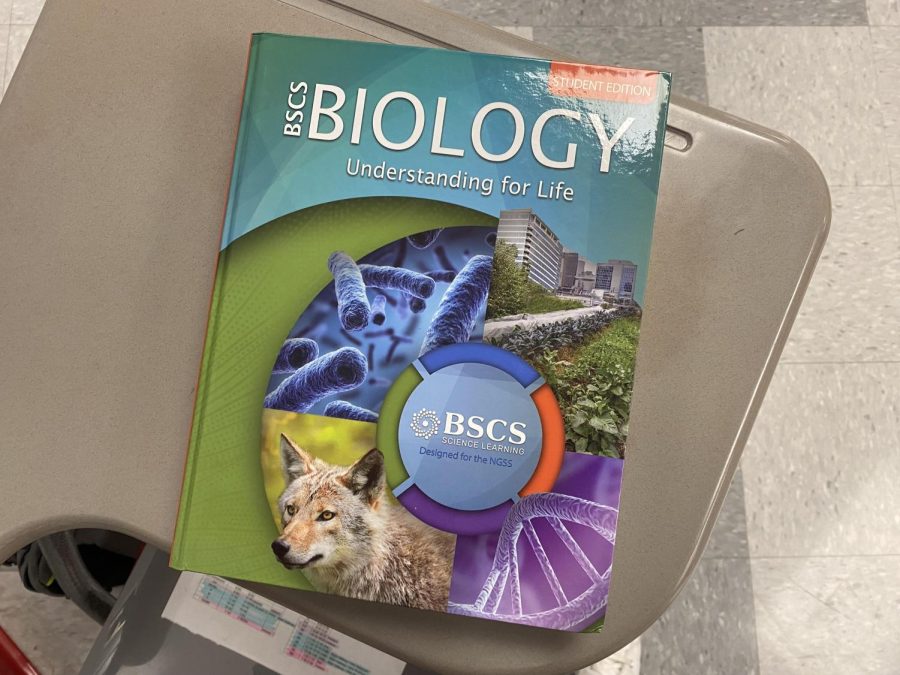

The new biology textbook is one example of a recent curriculum change.

For as long as anyone can remember, sophomores have taken biology at BSM. In fact, BSM rarely has major curriculum changes. However, with the biology department switching to a brand new curriculum this year, the process of developing curriculum becomes much more relevant.

Recently, the state standards shifted to recommend physical science for eighth grade curriculum. The BSM administration decided to seize the opportunity to take a more current approach to biology. The updated biology curriculum puts an emphasis on engaging with the concepts and using the scientific method, instead of the rote memorization common in past classes. “[The decision was made to move] to a more balanced approach which asks students to take in some content, but also engage in the science practices, which are the things that scientists do as well as engaging in cross cutting concepts, which is how scientists think,” biomedical science teacher Mark Peterson said.

Starting last spring, the biology department went through an extensive process to change the curriculum. First, former science teacher Stephanie Lauer did some research and reached out to the two main textbook publishers to ask for preview access. Then, the biology department settled on the newest iteration of the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS). After preliminary conversations, chemistry teacher Lisa Bargas, joined by Peterson and Director of Curriculum & Learning Steve Pohlen, met with salespeople to get cost estimates. Next, Bargas and Pohlen met with one of the authors of the textbook, and the decision was made. “And then eventually we did have some training where [the authors] came in, in August, after we made the decision and had a modicum of training on some of the systems and routines that make this curriculum different from previous curriculum,” Peterson said.

At BSM, curriculum development usually starts with the teachers. Since BSM hardly ever has large-scale curriculum changes, new curriculum would most likely come from new course ideas. Oftentimes, a department will suggest a particular textbook or even a course idea, which must then be approved by Senior High Principal Stephanie Nitchals. Sometimes, as in the case of the biology department, people like Pohlen who are active in the curriculum process will help choose a particular textbook for an existing course undergoing a curriculum change. “After that we bring it to the curriculum committee to determine how that would fit with the sequence of the rest of the thing. And then a group would come together to choose texts for that course,” Nitchals said.

As a private school, BSM has more freedom in choosing its own curriculum. “[Science teacher John Porisch] might have been involved in adoption in a public school before where it’s much more involved because of state laws and school boards and things like that, but I think that probably for our department, that’s probably pretty straightforward as far as how things work,” Peterson said.

The freedom of choice at BSM is similar to the college system, where professors are given little to no designated curriculum. And from science teacher Moni Berg Binder’s experience, curricula at the college she used to teach at depend on the professor. At St. Mary’s University of Minnesota Winona, teachers typically weren’t given a curriculum. They would get a book, with supporting materials like PowerPoint slides and suggested test banks, but the rest was up to them. “You know, different institutions work differently. My experience is based upon one institution that I came from that would do that kind of curricular mapping but, we weren’t given a curriculum so much as [we had to] work to develop one based on our expertise and knowledge,” Berg Binder said.