STEMinism

Empowering young girls to explore STEM fields is imperative to closing the gender gap in the sciences.

A study published in the Psychology of Women Quarterly in March 2016 found that women who study natural sciences encounter more sexual harassment, gender discrimination, and sexism in general compared to women who study social sciences. In a study published in Nature (a multidisciplinary scientific journal) that focused on researchers, women had to do 2.5 times the work of their male colleagues to receive the same peer review score for fellowships after they received their doctorates. Additionally, science faculty were more likely to hire men for lab manager positions when the male and female candidates offered the exact same credentials, according to a study discussed in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. So what drives women away from STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields?

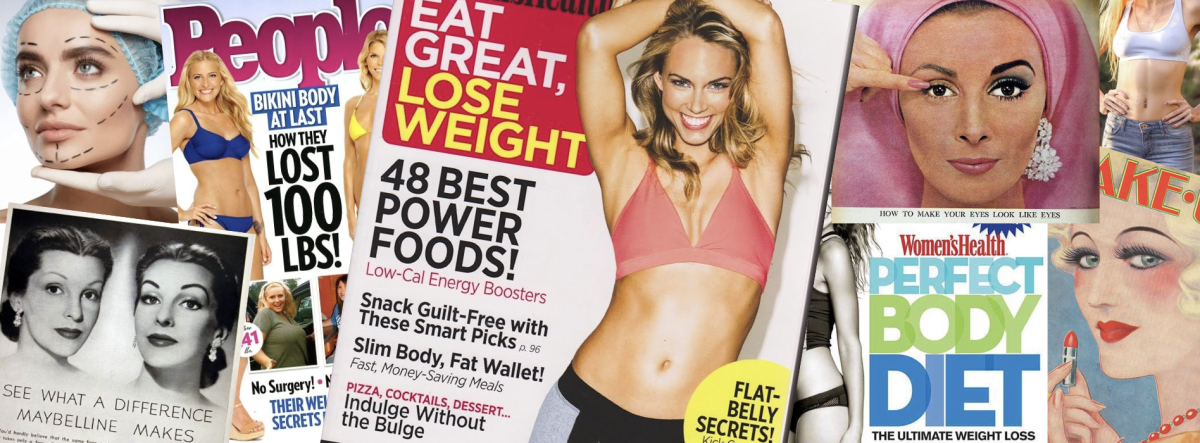

According to the aforementioned studies, it’s the extra energy that women have to put in to get the same recognition as their male counterparts. It’s the cultural-social misrepresentation of women that labels them as the “weaker sex.” It’s that women bring things to the table that some men may not consider or traditionally value, so they don’t receive the same level of respect.

Due to these factors, women often are underrepresented in engineering and other STEM fields, both in schools and in professional engineering. According to a study by Pew Research Social Trends, “Women continue to lag far behind men in the STEM industries of science, technology, engineering, and math. As of 2010, they made up 13% of employed engineers.” Furthermore, according to a Pew Research Study in January 2015, among undergraduates who were enrolled in engineering programs, only 18.6% were women.

Once women enter a STEM field, they face a significant wage gap. According to a National Science Board Science and Engineering Report of 2013, the median annual salary for highest-degree-holding women working full-time in science and engineering fields was $55,000, while their male counterparts earned $80,000. The widely-recognized wage gap is quoted to be as high as 80%, yet this report indicates that women working in science and engineering only make 69% compared to their male counterparts.

As much progress as has been made, it’s still a very heavily male-dominated field. It’s pretty obvious that there’s still a wide disparity, [and] I think it starts really young—girls are not encouraged to get into those STEM programs that are heavy on math and science. You’re very aware from a young age that it’s going to be an uphill battle.

— Sophie Herrmann

An article from the Journal Of Engineering Education reveals that because men are often associated with leadership, and women in the sciences face lower wages/gender discrimination, it is even more difficult for women to break through to higher roles. BSM Engineering teacher and department head Kirsten Hoogenakker has seen this struggle with one of her mentors. “I worked at EcoLab…it’s not like there weren’t women who worked there, but it was really hard for them to break through into the executive levels. One of my [former] bosses and mentors has really struggled in terms of navigating salary and finding a sense of equality, not only with her pay but also with her status constantly being questioned. And she’s like: ‘No, I promise, I have a doctorate; we are at the same place here,’” Hoogenakker said.

According to the same Journal of Engineering Education article, communication between men and women in engineering fields is often less effective due to gender discrimination. This creates a power imbalance and can give women a false sense of inferiority. And at the end of the day, the skill sets that women possess are irrelevant in a system that assumes gender conflicts with professional strengths and intelligence.

Junior Sophie Herrmann, who has been in BSM’s engineering program since she was a sophomore, sees the obstacles that women in engineering face every day from the experiences of her older sister Emily, a 2012 BSM graduate who is now pursuing a degree in industrial engineering. “As much progress as has been made, it’s still a very heavily male-dominated field. It’s pretty obvious that there’s still a wide disparity, [and] I think it starts really young—girls are not encouraged to get into those STEM programs that are heavy on math and science. You’re very aware from a young age that it’s going to be an uphill battle,” Herrmann said.

Further, the confidence gap is arguably the most powerful reason why there are few women in engineering and science fields. According to an article entitled Engineering by the Numbers, “because engineering is a traditionally male-dominated field, women may be less confident about their abilities, even when performing equally.” That feeling transcends age and experience for many women. Herrmann recounts doubting her STEM abilities as early as seventh grade when she was placed on the honors/ advanced math track. “I spent hours for an entire month telling my mom that I was in the wrong place. I asked her to go talk to the teacher and make sure that I was in the right math. I think this is an experience that a lot of girls have when going into a field like engineering… when you realize that you’re in the minority and that what you’re doing is not what’s expected of you, it’s really easy to get discouraged and think that you don’t belong. There’s this overall feeling that you’re not good enough, and a lot of talk that women in engineering are given handouts, or a leg up, don’t deserve to be there, and aren’t a part of the conversation a lot of the time,” Herrmann said.

To understand why these gender stereotypes still exist, many look to the not-so-distant past when a woman’s role in society consisted of raising a family and keeping a household. Although many college programs now push for more women in engineering, the gap is closing very slowly. “It’s a cultural-social thing, and it’s systemic. The first step is recognizing that it’s there, and we know that women are disproportionately represented in engineering. Colleges are pushing hard to get scholarships for girls, to make sure that their percentages are a little higher… [while] it’s nice to be able to brag and say that we have more girls in our engineering program [at BSM] than most colleges, it’s still difficult,” Hoogenakker said.

Though women still face the struggle of feeling underrepresented in a field as vast as engineering, they often find comfort by banding together with other women in similar situations. “[For women in engineering], I think that there’s a sense of struggle, but then there’s also a bond that comes with that… We like to support each other. And I think we recognize: oh, you’re here, and you’ve been through the same turning mill that I’ve been through. Now let’s get through this together,” Hoogenakker said.

Don’t let the boys boss you around. I think that’s the tendency, but be pushy about it. Be bossy. In the end, that’s what is going to make the difference; is to show the guys that you have it, you have what it takes, and to be confident about it.

— Kirsten Hoogenakker

Even seemingly small empowerments, like having Ms. Hoogenakker head BSM’s engineering department, draws more girls to the engineering program and encourages those already in it. “Since there’s such a small group of female engineers, you have a really tight bond with those women, and you’re all looking out for one another… that’s part of why I’m really happy that we have a woman heading our engineering program here; that’s been huge for me and I know the same for other girls in the program,” Herrmann said.

As far as girls who are just starting in engineering programs or considering joining, Herrmann emphasizes the importance of believing in your own abilities. “[My advice] is to find your confidence. Ground yourself in that, ground yourself in knowing that you are good enough. You deserve to be there, you deserve to be part of the conversation, and that you’re providing something unique and special. Know that you are good enough at math and science; just because you’re a woman doesn’t mean that you’re walking in with a disadvantage,” Herrmann said.

Similarly, Hoogenakker, who has experienced the struggles of being a woman in engineering in the workplace, encourages resilience and not letting others bring you down. “Don’t let the boys boss you around. I think that’s the tendency, but be pushy about it. Be bossy. In the end, that’s what is going to make the difference, is to show the guys that you have it, you have what it takes, and to be confident about it,” Hoogenakker said.

The benefits of having women as a part of the conversation, especially in influential fields like engineering, cannot be understated. “A big reason I chose to go into science was because I wanted a challenge—I wanted something that was going to be hard every day and that would change a lot. The more diversity you have in the workplace, not only are people, in general, happier in the end, but the product that you produce actually ends up being a lot better because you have many viewpoints going into something rather than just one,” Hoogenakker said.

Today, more women than ever look to test limits and push progress forward in fields like engineering. However, until our culture changes its perception of the abilities of women, progress will only continue slowly.

In the future, engineering must equalize the number of men and women in positions of power, to inspire young girls to pursue their dreams and potentially change the world. “When you see another woman trailblazing and going somewhere that isn’t necessarily expected, is outside of the box or untraditional, I think that is super powerful for other women. It starts a chain reaction of progress, and seeing a woman in a traditionally male-dominated role can affect other women as young as toddlers,” Herrmann said.