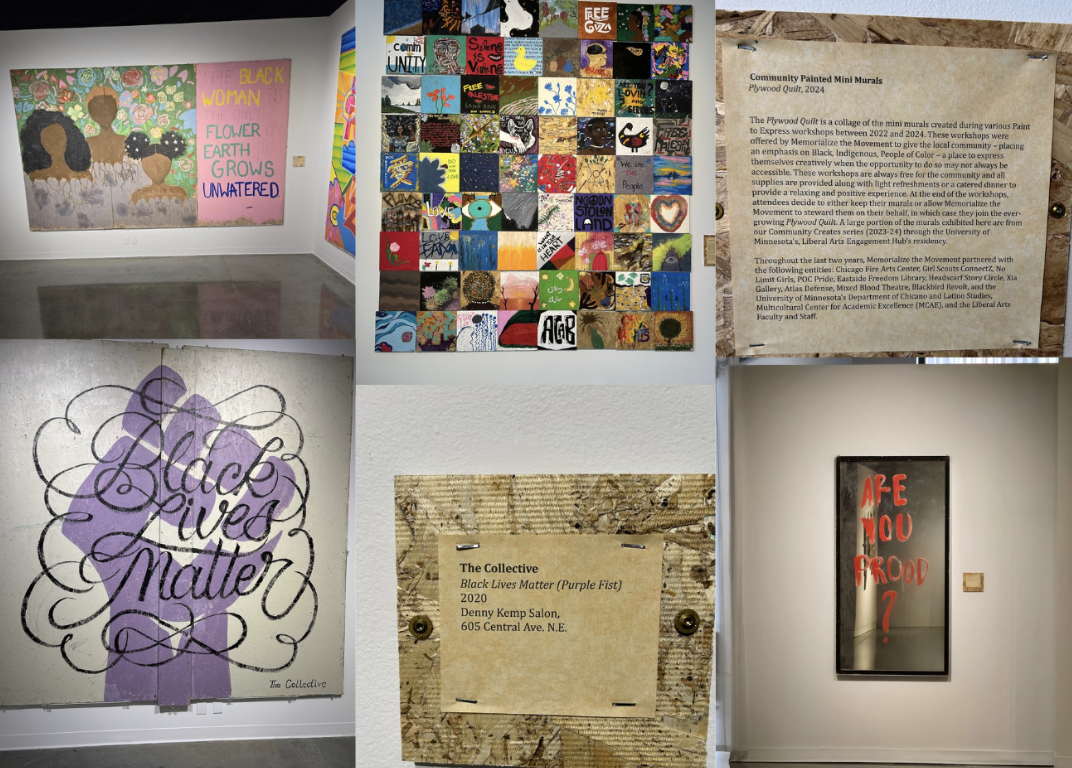

David Bowie says goodbye with final album “Blackstar”

Photo Courtesy of Columbia Records

Pop-rock artist and icon David Bowie released his farewell album “Blackstar” on January 8 full of haunting experimental music.

February 3, 2016

“I can’t give everything away,” David Bowie laments on the final line of “Blackstar,” acknowledging his impending death and the fact that this record will very well be the last he has to give away. On “Blackstar,” Bowie wildly experiments, fusing jazz music with electronic in a sonic palette that’s being dubbed “jazztronica,” and the resulting effect is a hauntingly compelling set of eight songs.

Now that Bowie has passed, just two days after the release of this record and his 69th birthday, “Blackstar” is thrown into a new light––one of a man who knew that death was coming. And, regardless of his death, this record would have always been viewed in the shadow of his legacy––a singular one, unparalleled by any other pop or rock artists in his time. Yet, even when seen in the shadow of his legacy, “Blackstar” shines as an exciting and unique addition to his canon.

Lyrically, the record focuses most unsurprisingly on mortality and the afterlife as well as on the rest of Bowie’s life and career. On “Lazarus,” he ponders the freedom that death will grant his soul––“This way or no way/You know, I’ll be free/Just like that bluebird.”––On the same track, he also recalls key events in his life, subjecting them to his new perspective of a dying man reflecting on time that could have been better spent:–“By the time I got to New York/I was living like a king/Then I used up all my money.”

“Blackstar” is most easily compared to Bowie’s Berlin-era record, “Low,” as it is similar in both level of experimentation and in the combination of both synthesized and traditional rock and jazz instrumentation. For this record, Bowie drew influence from Kendrick Lamar’s genre-spanning 2015 concept record, “To Pimp a Butterfly,” as well as IDM artist, Boards of Canada, and experimental hip-hop group, Death Grips. “Blackstar”’s producer, Tony Visconti, explained within an interview with Rolling Stone that “the goal was to avoid rock & roll.”

While Bowie tried to avoid his past musical efforts in order to pave a new trail for “Blackstar,” there are what seem to be musical allusions dispersed throughout the record. The harmonica on “I Can’t Give Everything Away” echoes the harmonica on the 1977 instrumental track, “A New Career In a New Town,” and the melancholy “Dollar Days” is hardly dissimilar from other gloomy Bowie tracks like “Five Years” or “Ashes To Ashes.”

These allusions suggest that Bowie was attempting to encapsulate an entire career with this record, while simultaneously giving fans a notable record that can stand up tall alongside the rest of his works¬––and he pulled it off.

Throughout his career, Bowie has shape-shifted to meet the appearance of his many alter-egos:––the glam-rock star who communicated with extraterrestrials, Ziggy Stardust, the lad insane, Aladdin Sane, and the Thin White Duke, to name a few, and now he has given us one more, the “blackstar.”

The “blackstar” (a gravitational object composed of matter) is not likely an alter-ego, but rather the very essence of Bowie’s artistic self, the center point from which all his works revolve, just as Bowie sings on the title-track: “At the center of it all is a solitary candle.” Much like how a burning star collapses upon itself before it dies, Bowie has done the same, heading to the “center of it all” before saying farewell.