Memoir of a twelve-year Spanish student…

Last year my family went on spring break to Isla Holbox, a small coastal island north of Cancún, Mexico. I was excited to finally use my armada of Spanish in the real world. Upon arrival I stormed off the plane with a tenacity only comparable to Miley Cyrus hopping of the plane at LAX with her dream and cardigan. Sadly, there were no locals exclaiming “Like who’s that gringo that’s droppin’ lingo” because to my surprise I could not ask for a taxi, I could not give directions; all I could barely do was order a plate of chips and guacamole. My mother was very dissatisfied, due to the fact that I was supposed to be the translator, and I was embarrassed that I could speak so little. I have taken Spanish classes for twelve years, so why can’t I speak Spanish?

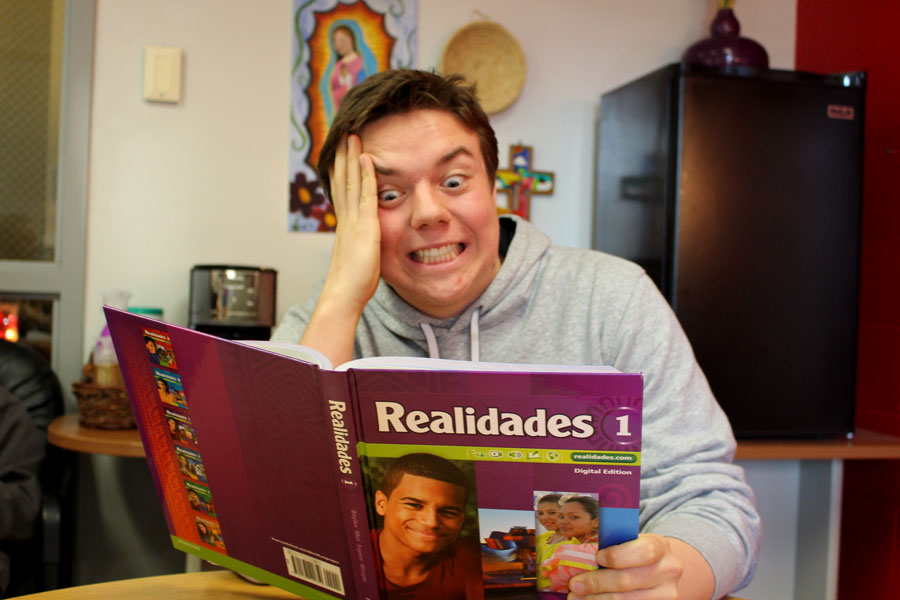

Lundberg laments over the emphasis on Realidades textbooks in Spanish classes.

Now, before my inability to speak is chalked up to a lack of effort or practice, I feel that I should state that I’ve received nearly all A’s in my Spanish classes, and am confident that most of my teachers would agree that good grades are a reflection of hard work and dedication. Let me also clear up the fact that my issue is not with the teachers, but rather the general approach that our school––and most of America––takes to learning a new language.

Looking across the pond, it’s undeniable that Europeans have collectively experienced more success in teaching students multiple languages. Their curriculums center around immersion, not filling out tedious online activities and memorizing irregular verbs, both of which may boost National Spanish Exam scores, but are not actually teaching students to speak another language. My vocabulary lists have included words like windsurfing, gang activity, affirmative action, and even slot machines––words that I hardly find myself using in English.

I sat down with Ms. Mary Murray, a Spanish teacher at BSM and Ms. Megan Hansen, the Language Department Chair, to discuss the effectiveness of BSM’s curriculum. While Murray and Hansen agreed that immersion is the best way to learn a language, they also defended the Realidades textbook used in Spanish levels one, two, three, four, and five. Murray noted that a curriculum centered around only speaking often leaves out other crucial pillars of Spanish: reading, writing, listening, and culture. She stated that she feels Realidades and BSM’s curriculum is preparing students in both a classroom setting and for real-world scenarios. However, I disagree. In my experience with BSM’s Spanish curriculum I have felt pressure to do well on tests, memorize prepared sentences to present to the class, but not to think on my feet and speak confidently in a real-life scenario. In fact, most speaking presentations involve reading off a prepared script or memorizing answers to pre-listed questions.

This past year I made the decision not to take a Spanish class at BSM, but I wasn’t ready to let the language go. I couldn’t stomach ending my twelve year Spanish career without knowing how to speak confidently. My mom had taken German lessons with a company in Edina called Berlitz, which specializes in teaching languages through conversation with a native speaker. My mother signed up my sister and I for hour and a half lessons three times a week all throughout summer. We spent the classes talking in Spanish with Alejandra, our native Argentinian instructor, about our favorite shows, our mutual obsession with the Kardashians, and most importantly, learning how to speak Spanish. The grammar and vocabulary knowledge from BSM did make the class a lot easier, but I gained more confidence in my speaking skills in those three months than in my entire previous 12 years of Spanish.

Besides updating their material, Berlitz’s general principles have remained very similar for over a century. Berlitz centers its conversational curriculum around five parts: a focus on speaking, active participation, immersion in the target language, a building-block approach, and native-fluent Instructors.

It’s clear that Realidades and Berlitz do overlap in some teaching methods: both utilize a building block approach involving moving from simple topics to complex ones, and concrete to abstract ideas. The biggest difference comes in areas of speaking and writing. In my opinion, the ratio of speaking to writing was flip-flopped in both curriculums. Berlitz has a lot of speaking with bursts of writing, while Realidades has loads of writing with scattered oral activities. I guess the decision between the better of the two just comes down to which aspect one values more, writing or speaking, personally, I prefer the latter because if I’m ever stranded in a foreign country, the only writing I’ll ever need is S.O.S.

Even after three months of Berlitz, my Spanish is still nowhere near perfect, but I was able to finally speak what I had written on paper at BSM. I feel that our curriculum needs to prepare students to speak Spanish on the fly, without overthinking simple phrases; even after four years of 40 minute classes nearly 165 days of the year, I still panic when asked the simplest questions. So, until I can master Spanish it will only ever be, as according to Miley Cyrus, a “Party in the U.S.A.” Fun Fact: I’ve taken Spanish at BSM long enough to listen to that song about 7,543 times, but I memorized the lyrics after just three, and I never wrote them down on a worksheet or studied them on Quizlet; I just sang along.

*In a now-deleted Facebook post by the Knight Errant promoting this story, the experiences of all students with the Language Department were generalized. We would like to publicly apologize for this statement and reinforce that this article is the opinion of one student, not the entire student body.