The Hmong Community: Past and Present

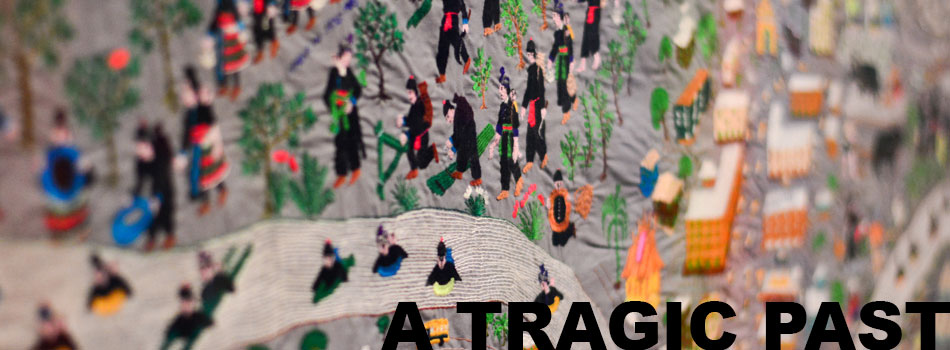

“My father-in-law was a soldier on the front line. When the US pulled out of the war, he ended up having to take his family and run, and live in the jungle for many years. Many families swam across, and many, many families died in the Mekong River. If you were Hmong, you were being shot and murdered,” Bee Vang-Moua, Hmong Language teacher at the University of Minnesota, said.

May 29, 2015

After the United States pulled out of Laos in 1973, the Laotian government began to kill the Hmong––a minority ethnic group that historically inhabited the mountainous regions of Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam––in an aggressive campaign. “All the Hmong were still left, and they were being ethnically cleansed,” Vang-Moua said.

Like many Hmong, Vang-Moua’s family was forced to flee through the jungles of Laos, traveling through the night and resting during the day, to stay out of the sight of North Vietnamese soldiers. “When the Hmong were making their way through the jungle, they had to give opium to the babies, or else if any of the babies cried, it would give away the whole group,” Vang-Moua said. “Many times too much opium was given because they would cry––a lot of babies died.”

Once across the Mekong River, the Hmong were free from the danger of the Laotian army, but many were not eager to be airlifted to safety. “Because my father-in-law was a soldier, his family’s name came up to get airlifted to the US, but he didn’t want to leave because his mother and his father were still in Laos, and he was hoping one day to go back and rescue them,” Vang-Moua said. “So they stayed until 1994, when the temporary refugee camps in Thailand were closed, and their only options were to move to US or France, or go back to Laos.”

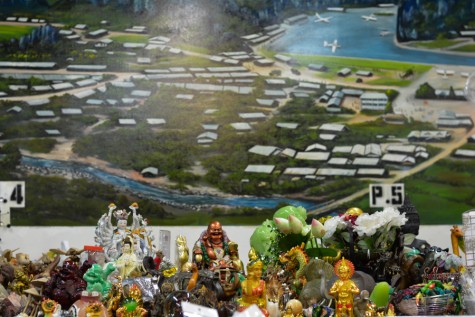

A Mural of a refugee camp is painted behind figurines for purchase at the Hmong Cultural Center.

Conditions in the camp were cramped and overcrowded. There were so many people packed into one area that even grass couldn’t grow—something that presented a problem for an agricultural people accustomed to growing food in the mountains of Laos. “There was barbed wire all around the camp, and we were not allowed to leave at certain time periods,” Vang-Moua said.

Living accommodations were small, primitive, and compact. “[There were] sort of like sheds, that were partitioned off for the families,” Vang-Moua said. “I remember the one that we had had a roof that was made out of tin, and when it rained it would make a lot of noise. Now, when I am in my car and it rains, it is very calming for me and very nostalgic.”

Life in the refugee camps varied between families based on their socioeconomic status. Vang-Moua, whose father spoke five languages and owned a small photography shop within the camp, was fortunate. “We were considered well-off in the camps because he had a business, so our experience was not as bad,” Vang-Moua said.

When the first wave of Hmong refugees came to the United States in the early 1980s, the government’s resettlement plan was to distribute the refugees amongst all 50 states. But when the second wave came, and the Hmong heard that those in Minnesota were thriving, in part thanks to organizations that already existed in Minnesota; therefore, many more Hmong chose to follow. “I think if we look at Minnesota as a state overall, with Catholic Charities, and different organizations that help refugee families or immigrant families, Minnesota just attracts more Hmong,” Vang-Moua said.

It didn’t matter if they were the farmer, the doctor, the teacher––they were no longer that: they were just another refugee.

— Bee Vang-Moua

The journey from the refugee camps of Thailand to a new life in the United States was filled with uncertainty. “Jobs were difficult to come across, and often times those with advanced education had to start from the very bottom because their education was not the westernized education,” Vang-Moua said. “It didn’t matter if they were the farmer, the doctor, the teacher––they were no longer that: they were just another refugee, living off the government.”

No matter who the Hmong were back in their country, and even if they had a full formal education and were working a high position job, once they were in America, all of that was erased. “[When my parents came here,] I think there was a lot of depression because my dad was literate, and he was fluent in all of these five languages, but he had a thick accent, so he was never hired in any high positions,” Vang-Moua said.

Some Hmong youth faced harsh bullying and exclusion, which led to a surge in gang activity in the late 80s. “Hmong kids were being picked on a lot, and then they joined gangs to make sure that people backed off and knew that you couldn’t pick on them because they could retaliate,” Vang-Moua said.

Today, the Hmong community is represented all over the Twin Cities, with the largest concentration in St. Paul. There are organizations such as the Hmong Cultural Center (HCC) that exist to provide the public with a better understanding about who the Hmong are and why they matter, as well as their history and culture. “We have a library that collects any books written about the Hmong,” Txongpao Lee, Executive Director of the Hmong Cultural Center, said.

The HCC teaches music and dancing, provides a program they call ABE, Adult Basics English, and assists in the traditional Hmong marriage and funeral ceremonies. “In our culture we believe that everyone has a spirit and soul. When a person dies, we need to have a certain ceremony to take the person’s spirit and take it back to his ancestors,” Lee said.

The University of Minnesota has also become a place for Hmong language and cultural celebration, home to the Hmong Student Association, which seeks to promote diversity and knowledge of the Hmong culture on campus. “We have different workshops and socials every month to promote an understanding and awareness of the Hmong culture. I feel extremely proud to be a part of the Hmong community, and I think it is important that people know who we are,” Karen Moua, Hmong Student Association President, said.

The Hmong have endured many trials, but their history and culture still remain, and thrive here in Minneapolis. “I consider myself Hmong-American or American-Hmong… I am both, and I feel like both are one in the same. I take pride in being Hmong and living here in the US, I take pride in knowing that we are here at all because this is one of the most successful and strongest nations in the world. I am very happy that, despite the things that happened––the warfare and those lives that have been sacrificed––that we made our way here to the US,” Vang-Moua said. Keenan Schember

Keenan Schember