May 29, 2015

After the United States pulled out of Laos in 1973, the Laotian government began to kill the Hmong––a minority ethnic group that historically inhabited the mountainous regions of Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam––in an aggressive campaign. “All the Hmong were still left, and they were being ethnically cleansed,” Vang-Moua said.

Like many Hmong, Vang-Moua’s family was forced to flee through the jungles of Laos, traveling through the night and resting during the day, to stay out of the sight of North Vietnamese soldiers. “When the Hmong were making their way through the jungle, they had to give opium to the babies, or else if any of the babies cried, it would give away the whole group,” Vang-Moua said. “Many times too much opium was given because they would cry––a lot of babies died.”

Once across the Mekong River, the Hmong were free from the danger of the Laotian army, but many were not eager to be airlifted to safety. “Because my father-in-law was a soldier, his family’s name came up to get airlifted to the US, but he didn’t want to leave because his mother and his father were still in Laos, and he was hoping one day to go back and rescue them,” Vang-Moua said. “So they stayed until 1994, when the temporary refugee camps in Thailand were closed, and their only options were to move to US or France, or go back to Laos.”

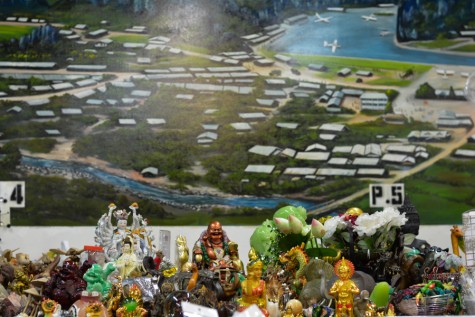

A Mural of a refugee camp is painted behind figurines for purchase at the Hmong Cultural Center.

Conditions in the camp were cramped and overcrowded. There were so many people packed into one area that even grass couldn’t grow—something that presented a problem for an agricultural people accustomed to growing food in the mountains of Laos. “There was barbed wire all around the camp, and we were not allowed to leave at certain time periods,” Vang-Moua said.

Living accommodations were small, primitive, and compact. “[There were] sort of like sheds, that were partitioned off for the families,” Vang-Moua said. “I remember the one that we had had a roof that was made out of tin, and when it rained it would make a lot of noise. Now, when I am in my car and it rains, it is very calming for me and very nostalgic.”

Life in the refugee camps varied between families based on their socioeconomic status. Vang-Moua, whose father spoke five languages and owned a small photography shop within the camp, was fortunate. “We were considered well-off in the camps because he had a business, so our experience was not as bad,” Vang-Moua said.