BSM Justice Club: the school-to-prison-pipeline is a problem that matters

Students wore pins today to raise awareness on the school-to-prison-pipeline.

November 14, 2014

Kiera Wilmot was 16 years old when a science experiment pushed her into the criminal justice system. She was arrested when her science experiment, an advanced volcano, went awry.

“When I put the aluminum foil into the bottle, the lid popped off and a little bit of smoke climbed out of the bottle. The principal asked what was going on, and I said: ‘Oh, it’s just a little science experiment,’” Wilmot said, “but then I was pulled out of class and taken to the discipline office, and was arrested there.”

Kiera’s charges included possession and discharge of a weapon on school grounds, and discharging a destructive device. While both have been dropped, it will take five years to clear each felony off her record.

Typically, one doesn’t associate school with prison––there are many more differences between the two than similarities. But there are links between education and incarceration that do exist in the form of a phenomenon known as the School to Prison Pipeline.

The School to Prison Pipeline refers to a set of “policies and practices that push our nation’s school children out of classrooms and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems,” according to the ACLU.

This year, the BSM Justice Club is working to break down the School to Prison Pipeline in the BSM community and beyond.

Beginning in the early 1970’s, a lack of funding and overcrowding of America’s public schools led administrators to seek solutions to major problems in the least expensive way possible, often sidelining children in the process.

Known as a “Zero Tolerance Policy,” resource strapped schools turned to “predetermined mandates” with severe punishments such as suspension and expulsion for a wide variety of actions, because they didn’t have the ability to handle inherent problems that existed internally. While a sad reality, this approach does not see children as individuals in need of help, but instead as problems that need to be suppressed.

Research indicates that as implemented, the Zero Tolerance policy is ineffective, resulting in increased dropout rates. One in-school suspension in 9th grade doubles a student’s chances of dropping out, and students that are suspended or expelled from school are three times more likely to come in contact with the juvenile justice system within the following year. In the process, students fall through the cracks, are punished, isolated, and pushed further and further from a school system without adequate resources.

Unfortunately, these statistics have become reality, with the number of suspensions increasing from 1.7 million in 1974 to 3.1 million in 2000. Rates indicate that this disproportionately affects students who have learning disabilities, children of color, students living in poverty and LGBTQ identified students — students who are already marginalized by society.

Of all students, 1/20 Caucasian, 1/14 Latino, 1/13 Native American, 1/6 African American, and 1/4 of African Americans with a disability will be suspended at least once during their educational career. According to the Centers for Disease Control, out-of-school youth are significantly more likely than in-school youth to engage in physical fights, carry a weapon, smoke, use alcohol and other drugs, and engage in sex.

The one-size-fits-all policy has doled out suspensions to students for surprising reasons, such as talking about a Hello Kitty Bubble Gun, hugging a friend, and chewing a pop tart into the shape of a gun. Students as young as kindergartners have been arrested for throwing temper tantrums, scribbling on desks, and, in Kiera’s case, science experiments gone wrong.

Over reliance on police to handle school misbehavior keeps law enforcement from focusing on dangerous threats to school safety — the very reason zero tolerance policies were enacted in the first place.

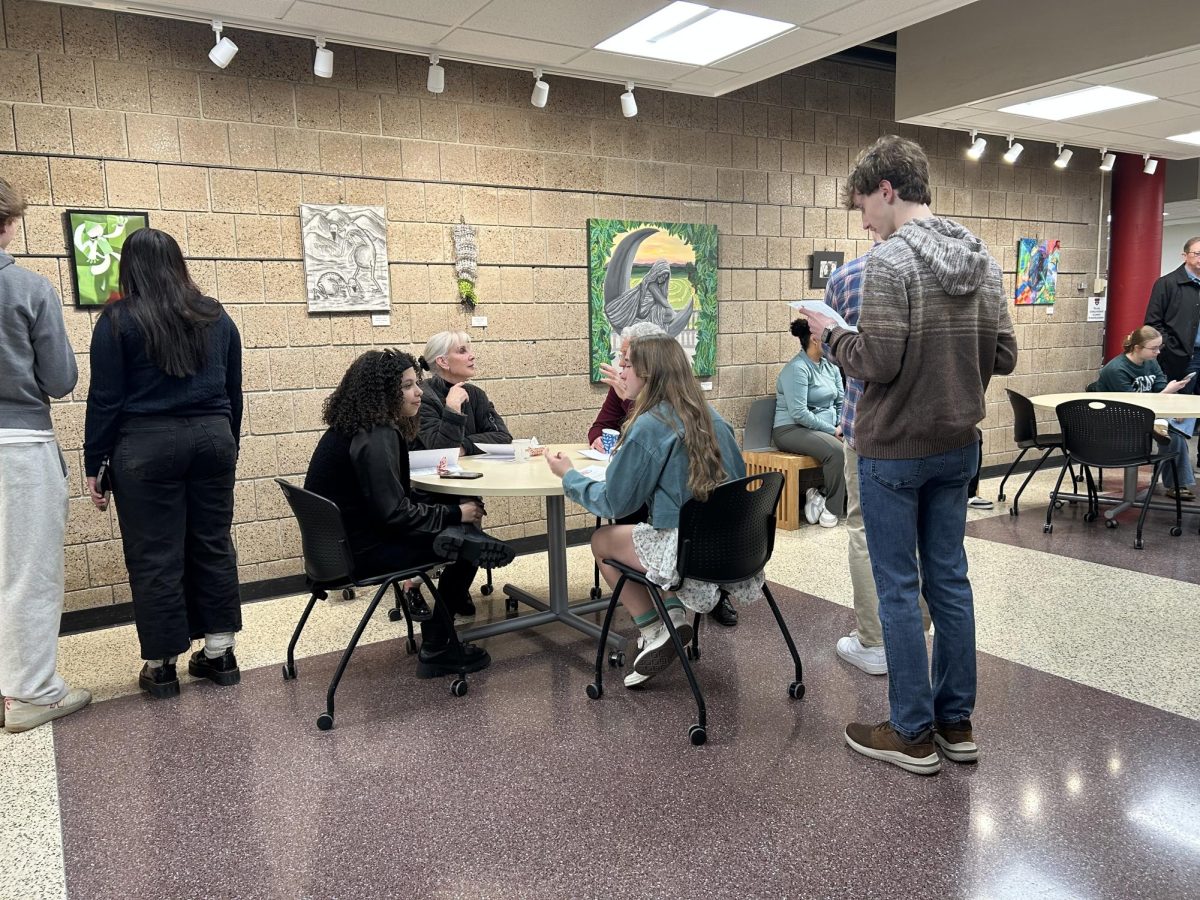

Through school announcements, lunch engagements, and an upcoming speaker panel, the BSM Justice Club hopes to raise awareness about this pressing issue. As a student, you may sign a petition at lunch, or come to the panel discussion Thursday, November 20 (3:00-4:00 PM in the Hamburg Theater) to learn how you can get involved.

We are often told that students are the future of our world, and they can’t be taught when they’re not in school. Students should be educated, not incarcerated.

“Honestly, I felt like a crazy person,” Kiera said. “They made me believe that I was a criminal.” No kid should be made to feel that way at school. Join the BSM Justice Club in working to make sure no kid ever has to.

![Teacher Lore: Mr. Hillman [Podcast]](https://bsmknighterrant.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/teacherlorelogo-1200x685.png)