Weighting AP Classes: A Bad Idea

BSM’s decision to weight AP classes starting in 2022-23 reflects a negative shift in the school’s educational policy.

As BSM adjusts to a new Principal this year, the school has already witnessed multiple alterations to core educational policies. Most notably, BSM has attempted to enhance their reputation as a “College Prep” school by dramatically increasing the number of options for students to earn college credit. This change demonstrates a desire to meet students where they are at academically, enhance their educational experience, and bridge the transition between high school and college academics.

Not all recent changes are similarly justified, however, as BSM’s decision to weight AP classes when calculating a student’s GPA betrays a regressive approach that is out of line with other advancements. This change goes against a long-held educational philosophy at BSM, against the well-informed concerns of students, and ultimately, against a growing trend across the US.

Personally, I’m not a huge fan of tradition. I think there is almost always room for improvement, which is why I have advocated for and supported many of BSM’s recent changes. But I also recognize that, in some cases, there is merit to the saying “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” This is one of those cases. BSM has historically made the conscious decision to weight all classes evenly, and as we will see, the school was way ahead of its time. So let’s look at why this change breaks the system, so to speak.

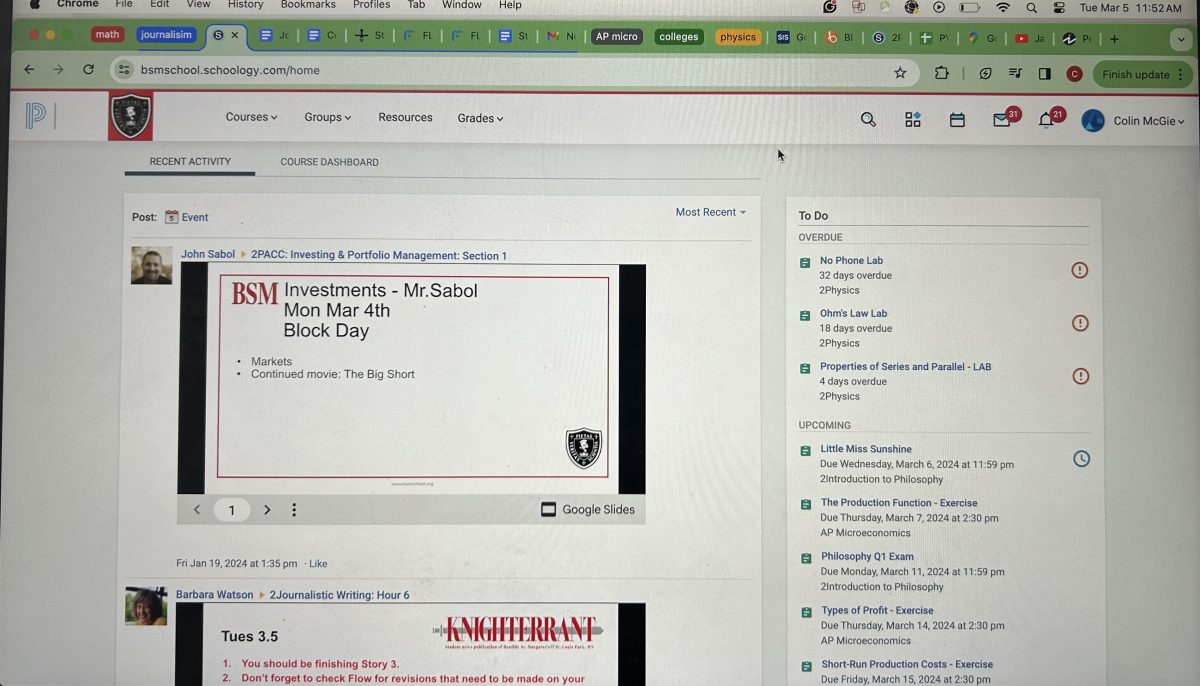

I’ll start with the issue that is easiest to address: application strategy. My understanding is that BSM will present two types of grades on people’s transcripts: weighted and unweighted. As a Junior, my transcript will show three years unweighted and one year weighted. If BSM cannot retroactively weight grades or is unwilling to display an unofficially weighted version, this change should be reserved for incoming freshmen.

By presenting two different weighting metrics, BSM reduces the utility of transcripts in three ways. First, it looks bad. This is relatively inconsequential, but regardless, I don’t want colleges’ primary source of information about me to look like a mess. Second, inconsistent application sets a strange precedent. I’ll return to this in detail later. Third, it impairs one’s ability to identify trends over time. For example, seeing a 3.8 one year, a 3.65 the next, and then a 4.3 and 4.02 sends incredibly mixed signals. A combination of weighted and unweighted grades makes analyzing broad academic trends over time unnecessarily difficult.

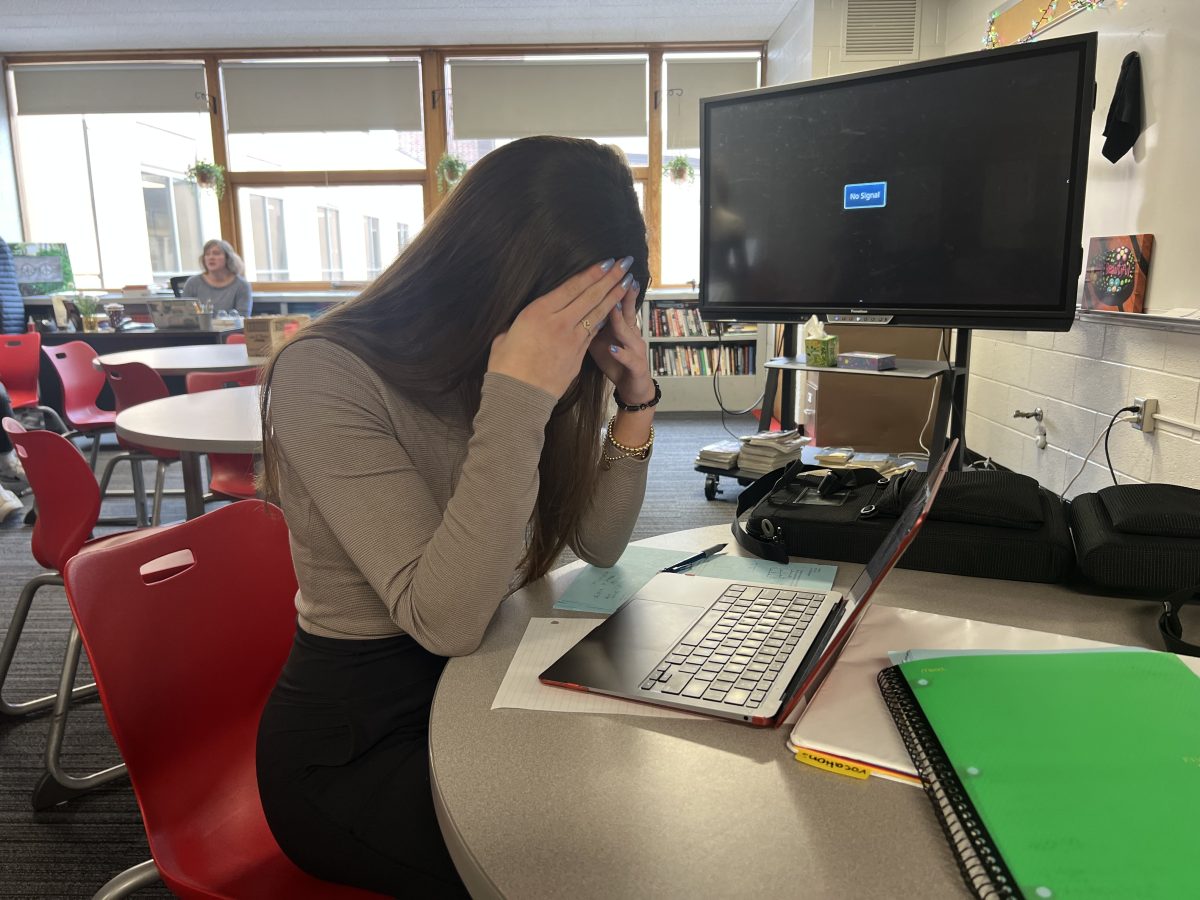

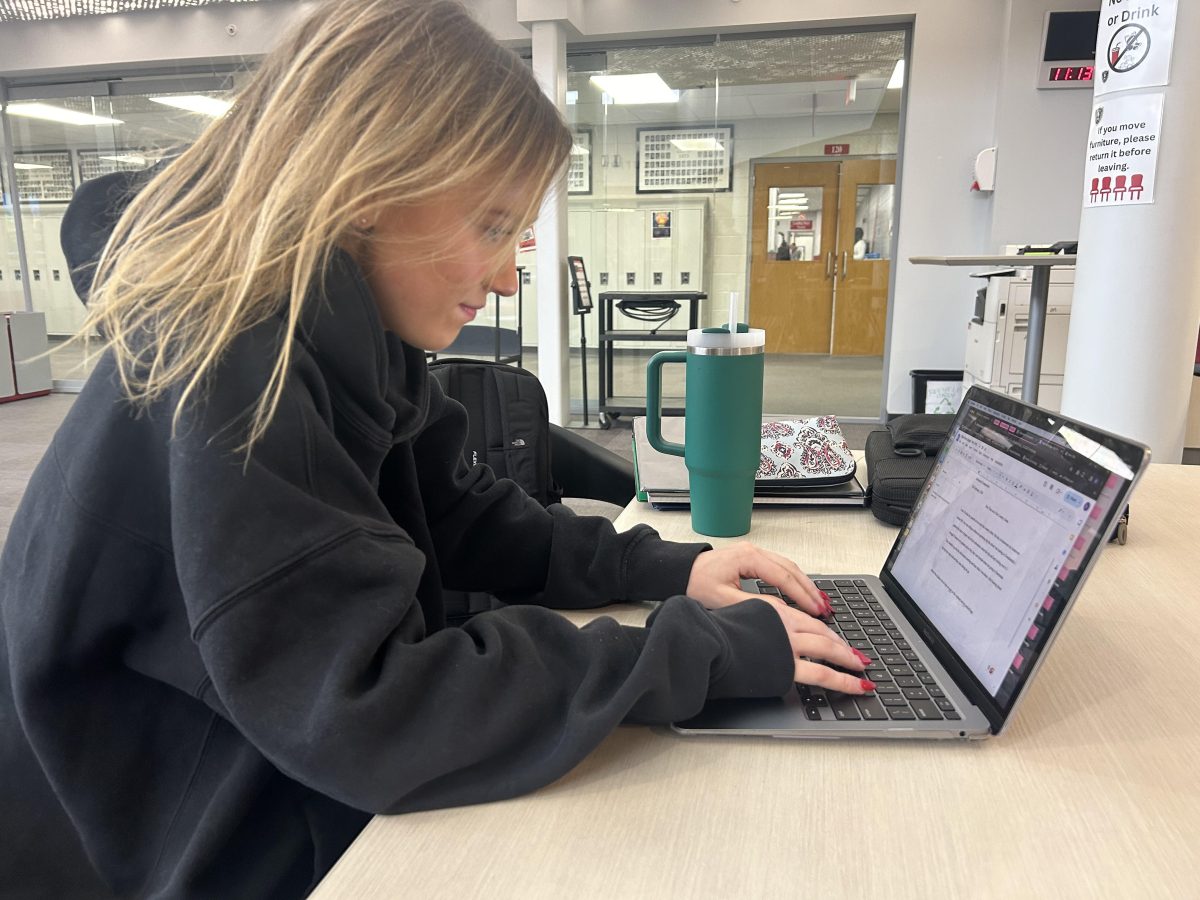

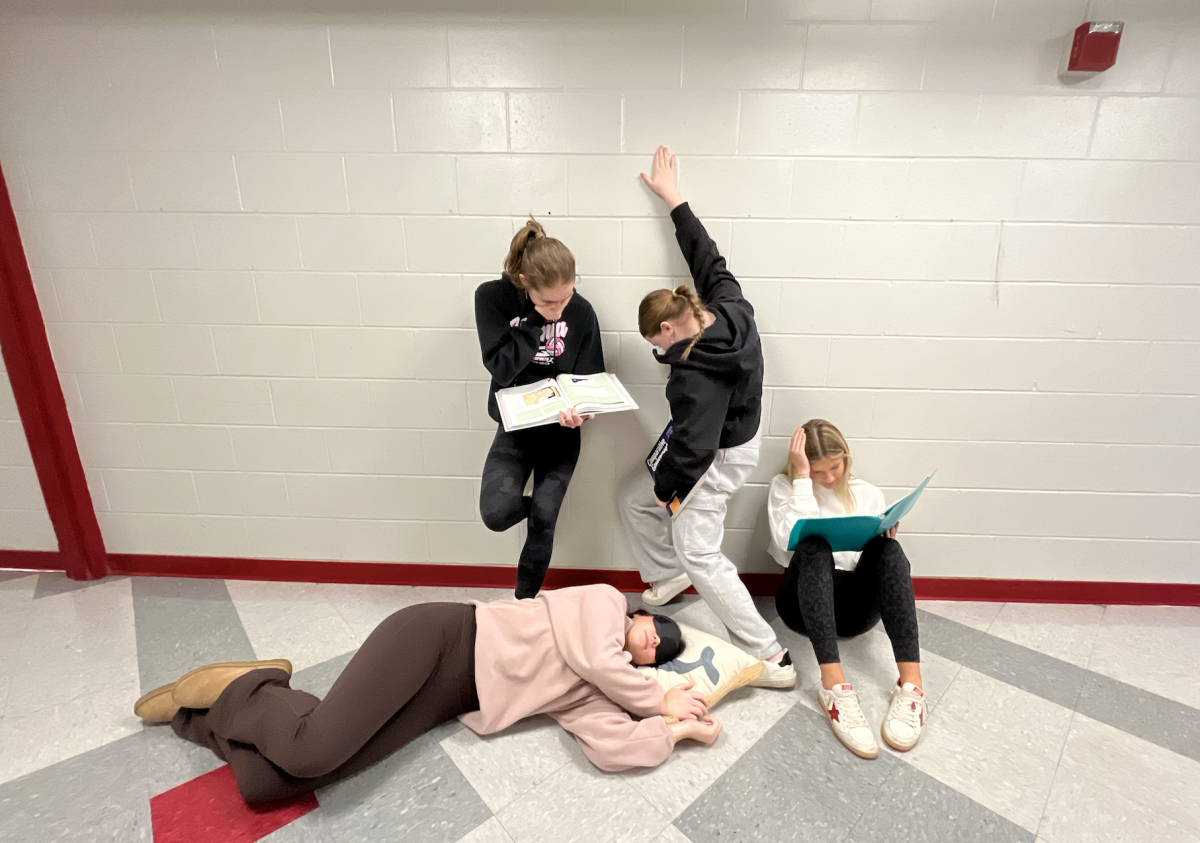

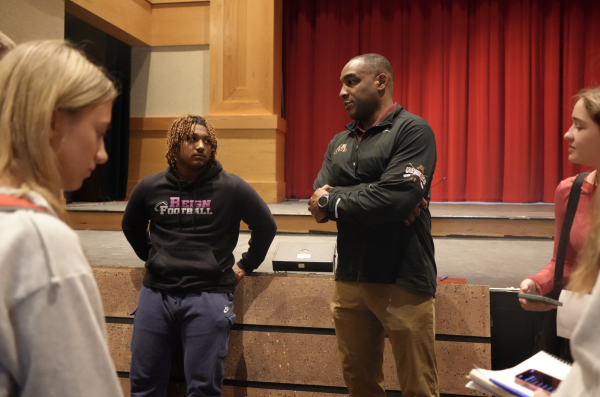

Due to increasing pressure from colleges, students are funneled into demonstrating “academic rigor” by taking the hardest classes, even when these classes may not be the right fit for them

Next, many teachers worry that extra emphasis on APs pushes students towards taking the hardest classes available and disincentivizes taking standard options. This trend already exists with Honors and AP classes. Due to increasing pressure from colleges, students are funneled into demonstrating “academic rigor” by taking the hardest classes, even when these classes may not be the right fit for them.

As an example, take AP Language and Composition. AP Comp, typically taken by Juniors at BSM, is many students’ first foray into the world of Advanced Placement. It is the logical progression from Honors English 10, but it also attracts many students looking to beef up their transcripts.

Teachers and students this year have noticed a disturbing decline in students’ writing (and reading) skills across the board. Essays are being returned with an unprecedented number of Cs and Ds. As BSM’s first year truly back to some sense of normalcy, it is important to acknowledge the role Covid-19 has placed in disrupting education. But this trend extends far beyond the pandemic. The issue isn’t necessarily about what skills students need to catch up on. Rather, it’s about what skills they never learned in the first place, or are unprepared to learn now.

Some students simply are not ready to take an AP by Junior year. This is not an insult, nor is it even an unpleasant reality. It simply is. Attempting to convince people otherwise – to condition them to the narrative of “academic rigor” – only sets students up for unnecessary failure.

Returning to the idea of inconsistent application, it is important to recognize the issues separating transcripts may create, especially in light of the added pressure to take APs that weighting inevitably brings. Proponents may argue that separation of weighted versus unweighted grades gives students a blank slate and that retroactively holding them to a higher standard is unfair. But what is even more unfair is pressuring students to rethink their entire academic philosophy in the name of GPA.

In 2019, the Knight Errant published an opinion piece arguing in favor of weighted grades. The author claimed that the current academic culture pushes students towards prioritizing grades over learning. This is true. What is not, however, is the claim that weighting APs disincentivizes caring about getting perfect grades. The actual impact is the exact opposite. If anything, students will feel pressure to take more APs to boost their GPA on the new scale. As we’ve already seen, this may pressure students into taking classes they are not ready for. The impact, as has been widely discussed by concerned high schoolers throughout the country, is a mental health crisis.

Taking too many AP courses risks causing undue stress and anxiety. Even unweighted, their intense workload, combined with pressure to excel, may cause students unnecessary harm. This situation is only exacerbated when APs are weighted.

Numerous high school newspapers have documented the effects this policy has, often calling for a reversal of current standards. A rise in mental health crises, poor school-life balance, and a toxic academic environment are all contributing factors to this perspective. BSM is unique, then, in that they are going against what seems to be a growing trend of unweighting APs across the US.

When schools decide to weight APs, they almost certainly do not want to harm students. In some cases, this change could enhance transcripts and provide an important datapoint that many colleges look for. Students applying to highly selective colleges may benefit from class rank or a GPA that accurately reflects the rigor of their coursework.

Personally, I would benefit greatly from weighted APs. As someone who will have taken seven AP exams by May of this year, showcasing this proof of rigor on my transcript is enticing. I, like many of my peers, look forward to the opportunity to compensate for a few lower grades with the courses I have prioritized throughout high school.

But the majority of BSM, and even a significant number of students who take APs, will not benefit like some others might. Not everyone will apply to schools that pay attention to class rank and care about APs, or at least, care about them as strongly as some. With this in mind, any benefit this policy may bring to a few students is easily outweighed by potential harm to many more, thus demonstrating that BSM’s decision to weight APs is a net detriment and regression from otherwise promising advancements in educational policy.