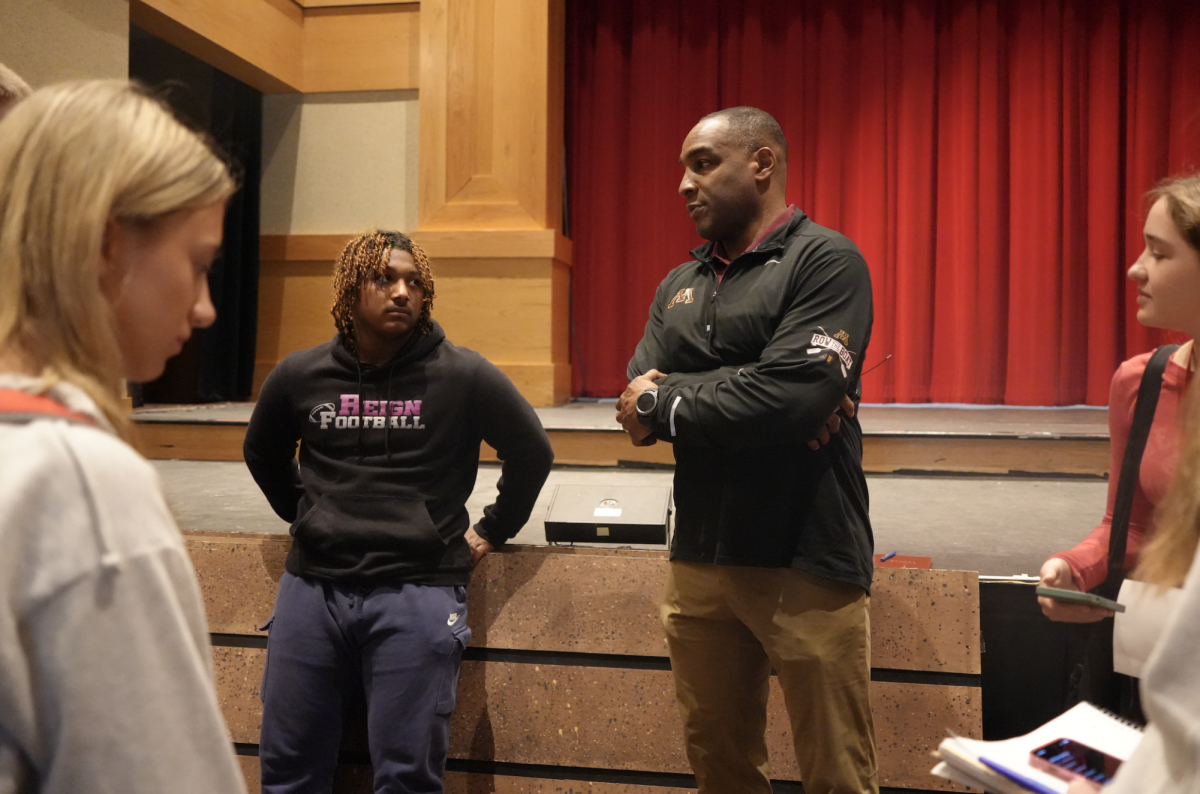

Science teacher Mr. Peterson uses different grading method

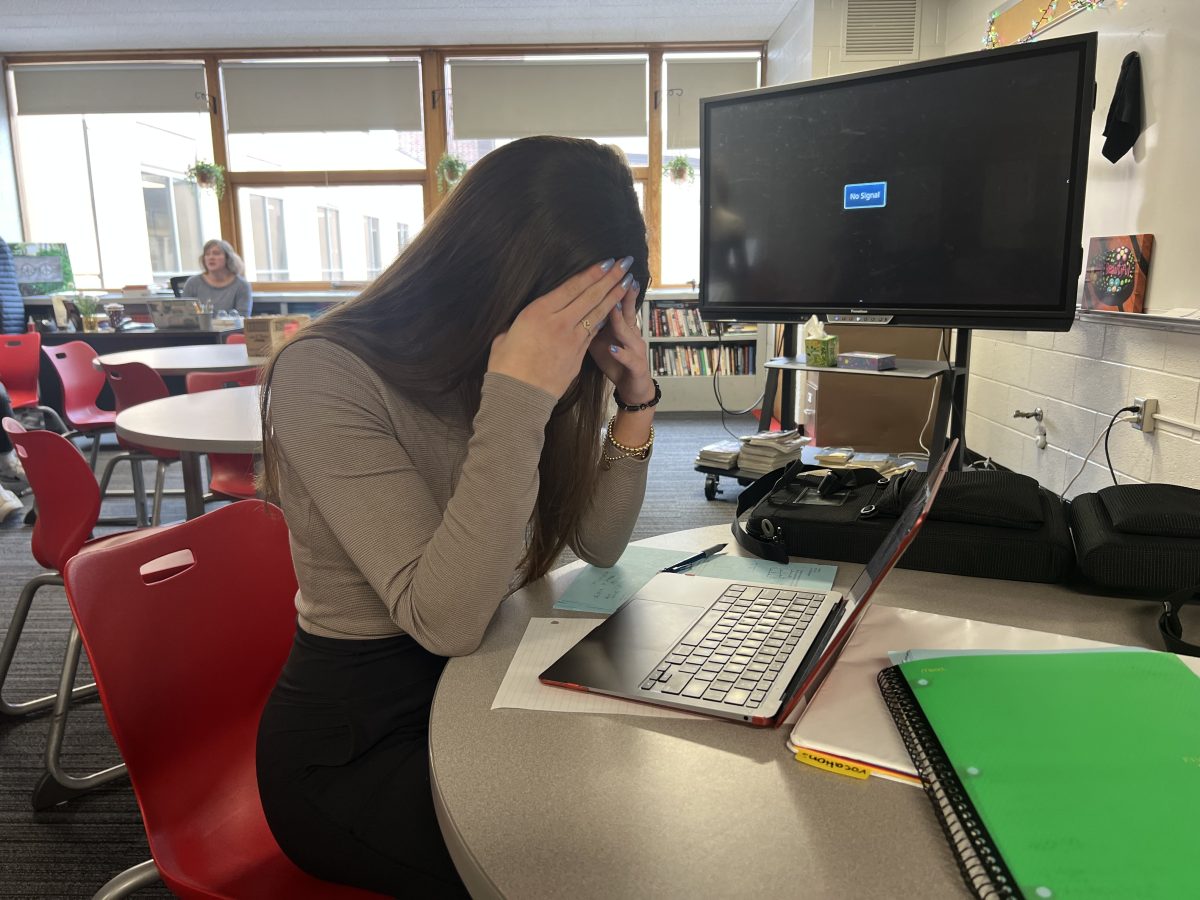

A, B, C, D, F. Since middle school or even younger, these benchmark grades are ingrained in students’ heads as a method for classifying their performance. However, BSM biology and physical science teacher, Mr. Mark Peterson has redefined this system, throwing out letter grades in favor of a method called standards-based grading.

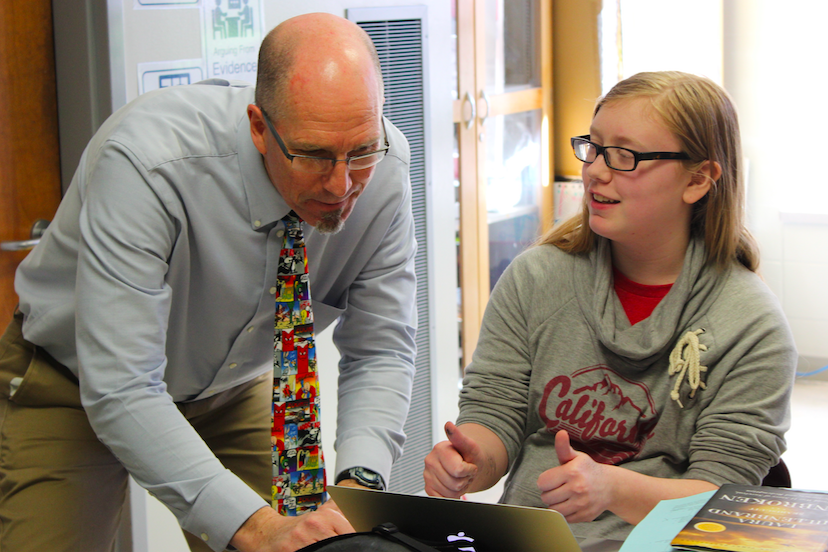

Mr. Peterson has been using a different grading method to better prepare students for the real world.

BSM science teacher Mark Peterson prides himself on a unique grading system that better evaluates students’ skills. Rather than basing grades on an accumulation of points throughout the semester, Peterson grades his students on their mastery of certain learning targets, skills pertinent to the subject. “I don’t want to accumulate a pile of points. I want to accumulate a pile of learning,” Peterson said.

Shifting to standards-based grading allowed Peterson to move away from marking students with a permanent grade on a topic they may just be beginning to understand. “Now, we go through iterations of a product, and by the time you’re done you’re really giving me your very best understanding for that particular learning target. That’s what’s going in the gradebook,” Peterson said.

Because the rest of BSM teachers use points to decide grades, Peterson does have to convert his students’ understanding to letter grades by the end of the semester.

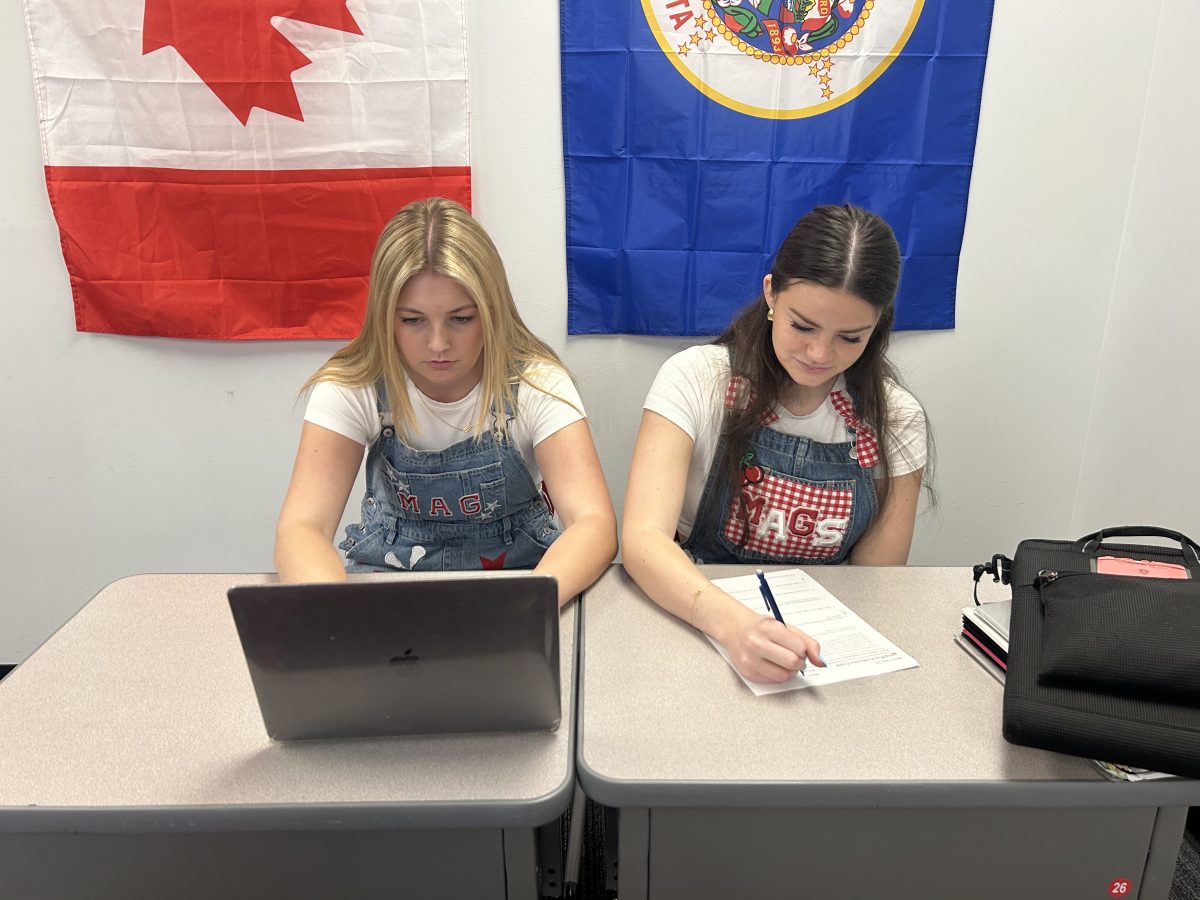

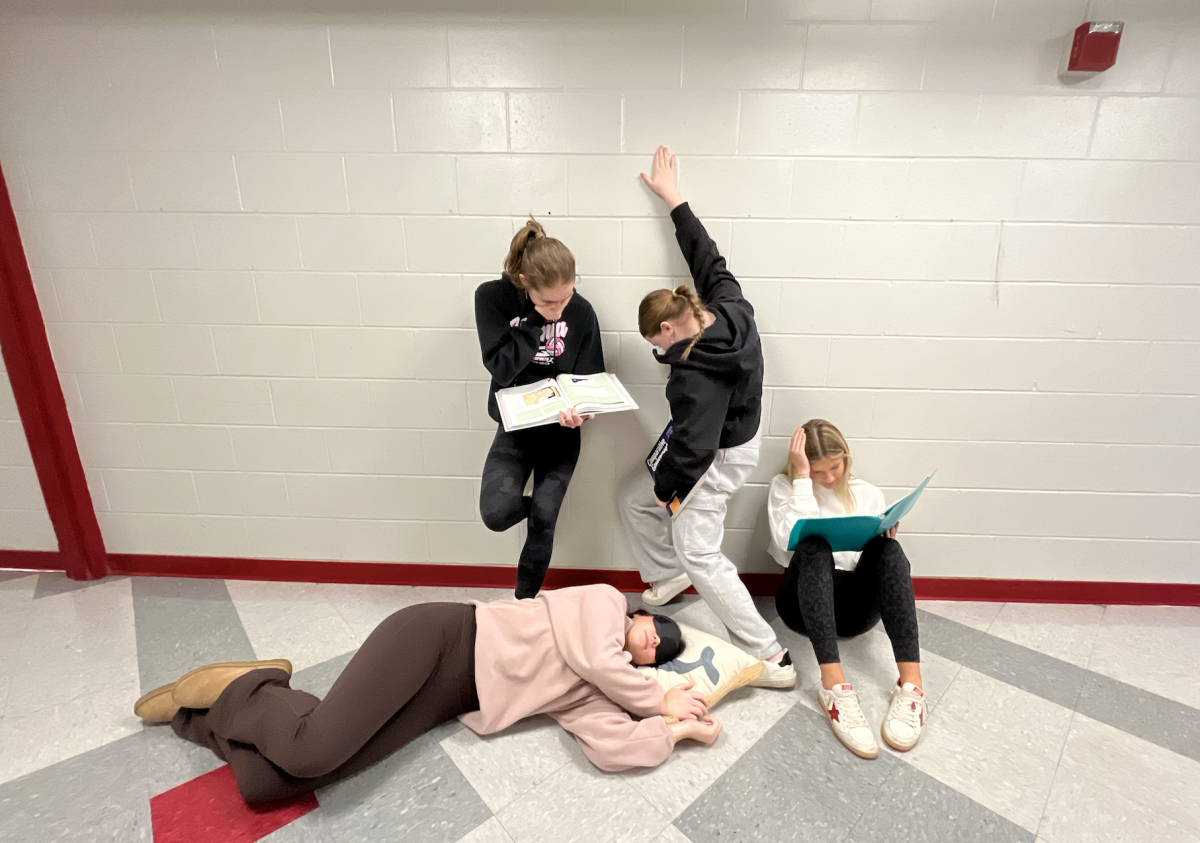

For example, a sophomore biology class was required to demonstrate understanding of the structure of a cell membrane. Their standard was: “I can create models to represent a system or part of a system.” From there, students had to show a mastery of that statement that Peterson approved of, whether that be a physical model, a computer animation, or any other method that demonstrates a complete understanding of the concept. “If a student doesn’t master the standard, the learning target, they keep working at it until they do,” Peterson said.

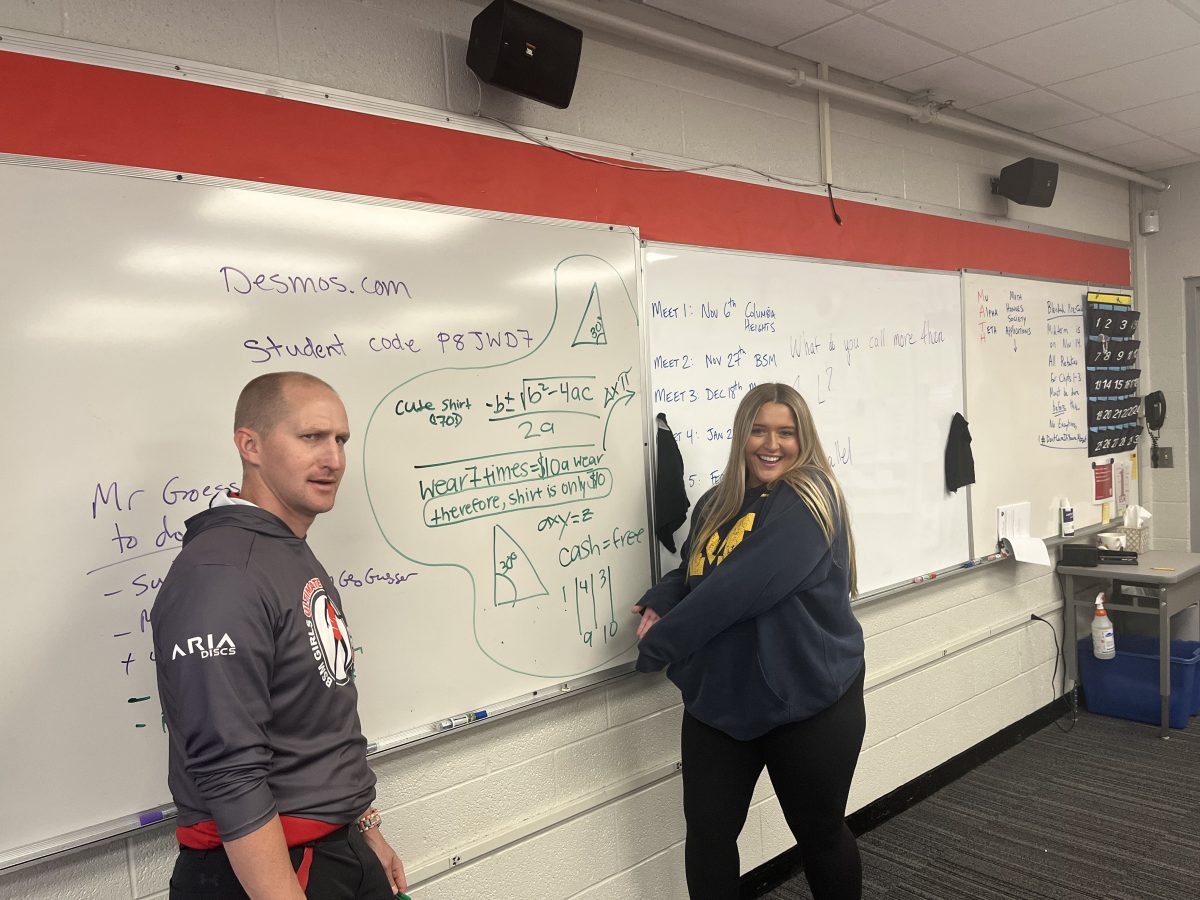

Peterson genuinely wants to make sure every student ends the class with a complete level of comprehension. To achieve this goal, he often works with his students on an individualized level. “Go back and learn it, if you’re really struggling, then we’ll sit down, pull out a white board and some markers, and we’ll figure it out,” Peterson said.

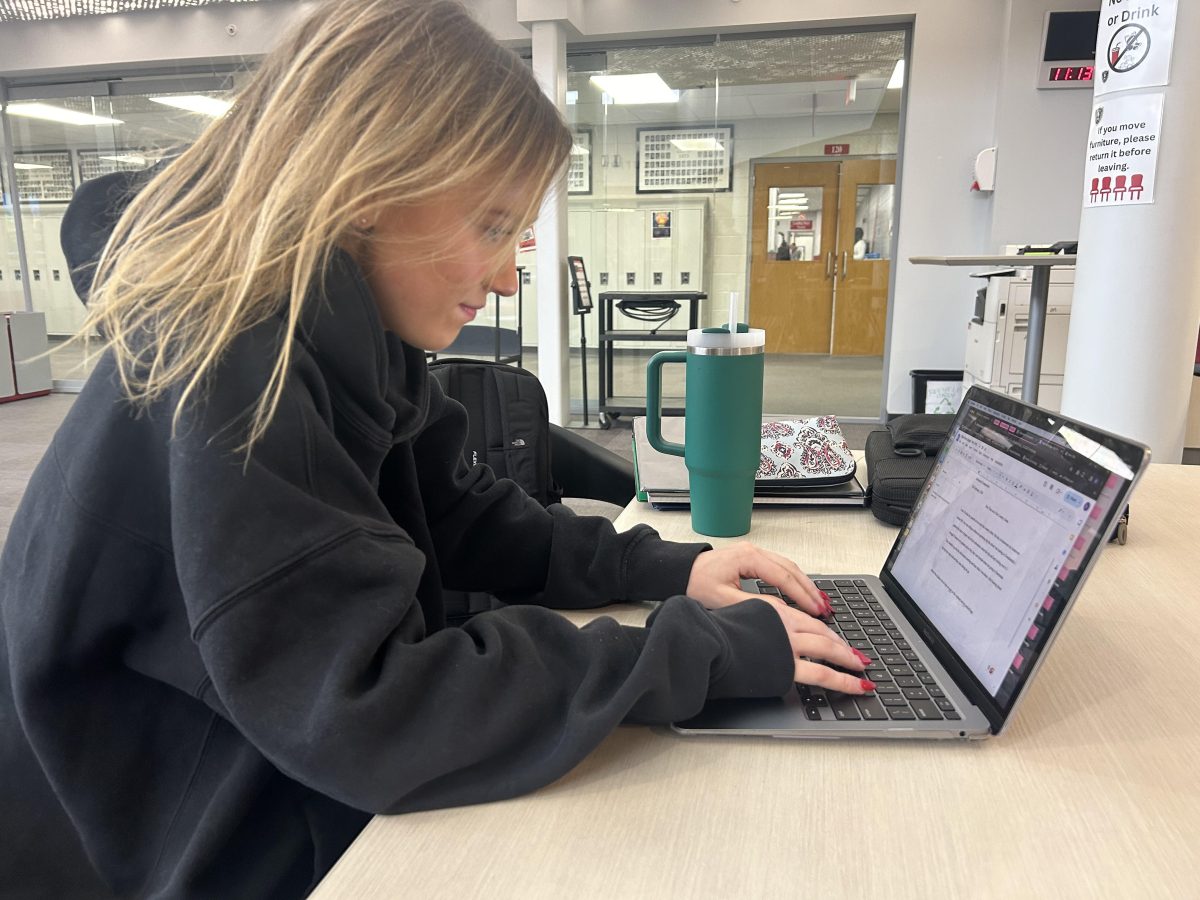

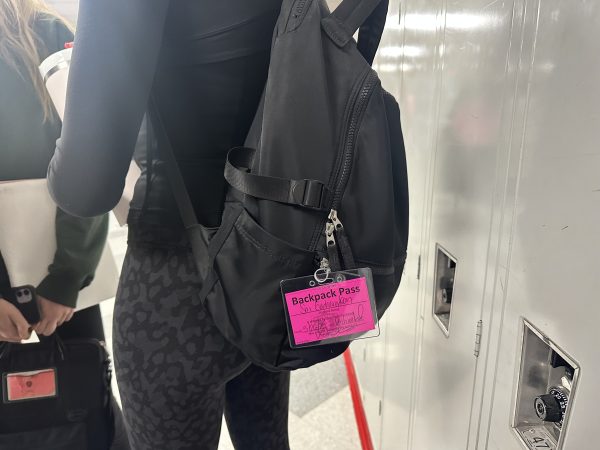

There are no penalties for late assignments in Peterson’s classes. He gives assignment dates as suggestions, but students have the entire semester to show they’ve mastered all the standards of a particular subject. Peterson understands that students are busy with sports, jobs, and other commitments. The main goal of his class is to learn the concepts, and if students can accomplish that, they are not penalized for how long it takes them to get there. “The penalty for students not getting their work done for me is to get their work done,” Peterson said.

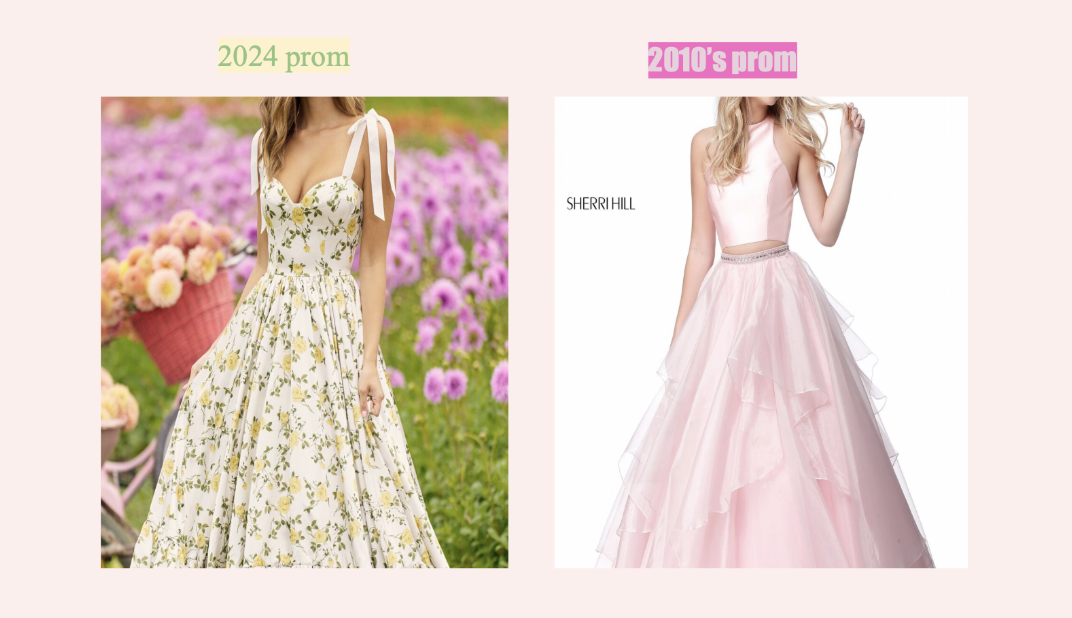

Although doing away with due dates and late grades is a far departure from most other classes at BSM, Peterson has not found it to impede on the quality of the class. “The due date for (ballpark estimate) 90 percent of the students is not an issue. Those ten percent, you just have to keep encouraging,” Peterson said. If you can teach the class about something that really shows me you understand the details, that’s an A. If you are proficient, that’s a B. If you have not met the standard partially proficient that’s a C. If you’re just beginning to understand, that’s a D. — Mr. Peterson

To help explain his philosophy, Peterson draws the comparison to a driver’s license. If a person hits the cone on the parallel park and fails their test, they go home, practice, come back a prove they’ve mastered the skill. Their license doesn’t say “driver’s license minus” because they hit the cone; it just took them longer to show mastery of the skill.

Peterson first learned about standards-based grading in the winter of 2011. He came across a blog post from a physics and calculus teacher in Iowa, Shawn Cornally. From there, he researched further, reading other articles, books, and blogs, formulating a plan to implement the system the following fall. At the time, Peterson taught at Dassel-Cokato High School. This is his second year at BSM.

When implementing the new system at Dassel-Cokato, Peterson was met with push back from parents concerned about how the new philosophy could potentially affect their children’s GPAs or how colleges would see the grades. “Once you sit down and talk with people about it, [they understand] it’s a different philosophy in the classroom, but it’s not,” Peterson said.

Because Peterson’s approach to grading is unique at BSM, it takes a lot of upfront education for students to understand how the class functions and how they will be assessed. Peterson has been met with frustration from some students who grasp a concept right away and feel they deserve a higher grade than the student that takes longer to understand, but ultimately education is not a race. Peterson’s goal is to make sure all his students reach a level of comprehension, and generally that concept is positively received by his classes. “Students like the idea of saying ‘you’re not on 100 percent of the time’ rather than saying ‘too bad for you,’” Peterson said.

Peterson knows that his philosophy could be applied in every subject area, and while he remains the only teacher at BSM to fully utilize standards-based grading, the success of Peterson’s approach has sparked the curiosity of his colleagues.